Darwin and Evolution

Dr. C. George Boeree

Darwin and Evolution

Dr. C. George Boeree

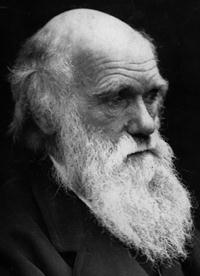

Charles

Robert Darwin (1809-1882)

Charles

Robert Darwin (1809-1882)

Charles Darwin was born in Shrewsbury, England, on February 2, 1809. His father was Robert Waring Darwin, a physician and son of the famous Erasmus Darwin, also a physician, as well as a respected writer and naturalist. His mother was Susannah Wedgwood Darwin. She died when Charles was eight.

Charles was educated in the local school, taught by Dr. Samuel Butler. In 1825, he went to Edinburgh to start studying medicine, but he soon realized that he did not have the stomach for it! So he switched to Cambridge, ostensibly to become a clergyman. He was actually more interested in entomology -- especially beetles -- and in hunting. He graduated from Christ’s College in 1831.

It is said that even when he was a young man, he had a patient and open mind, spending many hours collecting specimens of one sort or another and pondering over new ideas. The idea of evolution was very much in the air in those times: It was increasingly clear to naturalists that species change and have been changing for many millennia. The question was, how did this happen?

One of his mentors, John Henslow, encouraged him to apply for the (unpaid!) position of naturalist on a surveying expedition on the now-famous vessel, the Beagle, under the command of Capt. Robert Fitz-Roy. Charles left England for the first time in his life on December 27, 1831. He wouldn’t return until October 2, 1836!

Most of the ship’s time was spent surveying the coasts of South America and nearby islands, but it would also visit various Pacific islands, New Zealand, and Australia. It was the Galapagos Islands that most impressed him. There he found that finches had evolved a variety of beaks -- each suited to a particular food source. Natural variation had somehow been selected to fit the ecological niches available on the tiny islands.

Upon returning, Darwin wrote several books based on his surveys on geology and the plant and animal species he had observed and collected. He also published his journal as Journal of a Naturalist. He notes that he was most impressed by the ways similar animals adapted to different ecologies.

From early on, Darwin recognized that selection was the principle men used so successfully when breeding animals. What he needed now was an idea as to how nature could perform that task without the benefit of intelligence!

In 1838, he read a book by Malthus called Population. Malthus introduced the idea that competition over limited resources would, in nature, keep populations stable. He also warned that human populations, when straining resources, would suffer as well!

On January 29, 1839, Darwin married Emma Wedgewood, a cousin. They lived in London for a few years, then settled in the village of Down, 15 miles outside London, where they lived the rest of their lives. Darwin began suffering from an illness he had probably contracted from an insect bite in the Andes many years before. Darwin’s son, Francis, later could not say enough about his mother’s dedication to his father’s well-being. Without her, he would have been considerably less productive. They would go on to have two daughters and five sons.

Darwin wrote a sketch of his theory in 1842. In 1844, he wrote in a letter “At last gleams of light have come, and I am almost convinced (quite contrary to the opinion I started with) that species are not (it is like confessing a murder) immutable.”

He was about half done with a full exposition of his ideas when he received an essay from A. R. Wallace, with a request for comments. The essay outlined a theory of natural selection! Wallace, too, had read Malthus, and in 1858, while sick from fever, had the whole idea come to him in one flash. Darwin, in his reluctance, had postponed revealing his ideas to the scientific public for 20 years!

Darwin forwarded the essay to his friend, Sir Charles Lyell of the Geological Society, as Wallace had requested. Lyell sent the essay on, with an essay by Darwin, for presentation at a scientific conference.

The point they jointly made was clear: Just like men can exaggerate one or another minor variation by selectively breeding dogs or cattle, so nature selects similar variations -- by only permitting the most successful variations to survive and reproduce in the struggle over limited resources. Although the changes would be slight and slow, the millennia would permit the obvious diversity of nature! Darwin named this natural selection.

In 1859, Darwin finally published his master work, on the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection. The book was an instant success. There was also, of course, a great deal of debate -- mostly concerning the contrast with traditional religious explanations of the natural world.

Natural selection was often confused with an earlier idea of the French naturalist Lamarck. He suggested that characteristics acquired during an animal’s life were passed on to its offspring. The famous example is how the constant stretching of the neck over many generations explains the giraffe’s unlikely physique. This theory -- Lamarckianism -- was natural selection’s major competitor for decades to come!

In 1868, he published The Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication. Then, in 1871, he came out with The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex. This was really two books in one. The second part is about sexual selection. This is what accounts for, for example, the bright colors of many male birds: Both the males' coloring and the attraction to the coloring on the part of the females during courtship are selected for because these variations benefit the offspring.

The Descent of Man portion of the book is a brief introduction to the idea that we, too, are the results of natural selection. This part would lead to a lot of heated arguments!

In 1872, The Expression of Emotion was published. This time, Darwin talks about the evolution of the signals that animals use to communicate -- and relates those signals to human emotional expression. This is the first step towards what we now call sociobiology (and evolutionary psychology).

In addition to these influential books, Darwin also enjoyed studying and writing about plants. In 1862, he wrote Fertilization of Orchids. In 1875, he came out with both Climbing Plants and Insectivorous Plants. In 1877, came Different Forms of Flowers on Plants of the Same Species. In 1880, he wrote, with his son Francis, The Power of Movement in Plants. And in 1881, he published the famous Formation of Vegetable Mould through the Action of Worms!

Charles Darwin died April 19, 1882. He was buried in Westminster Abbey. He was apparently a kind and gentle man, beloved by his family and friends alike. Outside of his voyage on the Beagle, he rarely left his home in Down. Reluctantly, he surrendered his religious beliefs and settled into an agnosticism that did not prevent him from participating with his parish in charitable works.

Alfred Russel Wallace

Alfred Wallace was born in 1823 in the village of Usk in Monmouthshire, England. His options were limited as his father died when Alfred was still a young man. So, taking advantage of a natural talent, he became a drawing teacher.

He went on an expedition to South America with his friend Henry Bates. He spent four years in the jungles of Brazil. On his way home, the ship caught fire and sank -- with four years of notes and specimen collections. The crew and passengers were fortunately rescued by a passing vessel. These adventures were the basis of Travels on the Amazon and Rio Negro, published in 1853.

Soon afterwards, he left on a second voyage, this time to Malaysia. This one would last eight years! It was during this expedition that he, sick with fever, had the idea for natural selection, and in two days, wrote an essay on the topic and sent it off to Darwin. After his return from Malaysia, he published The Malay Archipelago, a detailed journal on the plants, animals, and people of the islands.

He died November 7, 1913. Although offered a place at Westminster Abbey, his family preferred that he be buried near his home. His grave is appropriately marked by a fossilized tree trunk.

Thomas Henry Huxley

Thomas Henry Huxley was born May 4, 1825, the son of George Huxley, a schoolmaster, and Rachel Huxley. He received two years of formal education at his dad's school, and was for the rest self-educated.

Although he was raised Anglican, he became interested in Unitarianism and its naturalistic thinking. This interest led him to begin studying biology with his brother in law. His studies led to a scholarship to Charing Cross Hospital in London, where he won awards in physiology and organic chemistry.

He served as assistant surgeon on the HMS Rattlesnake. which was surveying the waters around Australia and New Guinea. To pass the time, he began investigating the various forms of sea life.

Huxley met and fell in love with Nettie Heathorn in Sydney in 1847. He then continued his biological research in that part of the world. After returning to England, he was elected to the Royal Society in 1850, but could not find an academic position. Depressed and angry, he began taking on controversial stands -- including denial of the Christian version of geology.

In 1854, he began teaching at the Government School of Mines. Finally established as a gentleman, he brought the patient Nettie to England and they married in 1855.

Huxley met Darwin in 1856, and they developed a long and close friendship. He took it upon himself to begin a campaign for Darwin's theory, which earned him the nickname "Darwin's bulldog." In particular, he fought against the church and for the concept of human evolution from apes. All the while he was a great promoter of science in general and scientific education in particular.

Huxley was responsible for a great deal of research, from his original work on sea creatures to later work on the evolution of vertebrates. He also came up with the idea of agnosticism -- by which he meant the belief that ultimate reality would always be beyond human grasp. And he is responsible for the popular metaphysical point of view known as epiphenomenalism.

In 1882, his daughter went mad. She would die five years later under the care of Jean-Martin Charcot, the great French psychiatrist. He became very depressed and retired from his professorship. For a while, he promoted Social Darwinism (see below), but backed away years later to say, with Darwin, that humanity is best served by promoting ethics, rather than instincts.

He died of a heart attack during a speech, June 29, 1895.

Herbert Spencer

Herbert Spencer was born April 27, 1820, in

Derby, England. His

father

was a schoolmaster, and both his parents were "dissenters" (i.e.

religious

non-conformists). Spencer was clearly gifted and was mostly

self-educated.

An excellent writer, he wrote articles on social issues for various magazines of the day and even became editor of The Economist for several years. In 1855, he published The Principles of Psychology. This became part of a series of books, which he called The Synthetic Philosophy, and included biology and sociology as well as psychology.

Originally believing in the inheritance of acquired characteristics (Lamarckianism), he became a follower of Darwin's theory. It was, in fact, Spencer who coined the phrase "survival of the fittest" But he also transformed Darwin's theory into a social theory that encouraged extreme individualism and laissez-faire economic policies, called Social Darwinism.

Basically, survival of the fittest was to apply to people competing against people as well, and he implied that it was something of a social duty to accept the fact that some would be rich and some poor -- and that the consequences of poverty should not be interfered with. Even whole societies -- such as England -- were engaged in a struggle for survival that did not allow for weakness of will or sentimentality.

Social Darwinism is not something Darwin would have approved of. It has in it the fallacy of false analogy: Human society is not a neat parallel to the non-human biological world. Unfortunately, Social Darwinism seems to be here to stay, and can be found within Fascist, Conservative, and Libertarian political agendas, and in personal philosophies such as that of Ayn Rand.

Spencer is, nevertheless, considered one of the great productive thinkers of his day. He died Dec. 8, 1903, in Brighton, Sussex.

© Copyright 2000, Dr. C. George Boeree

(A major resource for Darwin's biography was the 11th edition

(1910/1911)

of the Encyclopedia Britannica, available online

here)