Learning

Dr. C. George Boeree

Shippensburg University

Learning

Dr. C. George Boeree

Shippensburg University

Learning

Whatever the instinctual component to human life, it is clear that learning is the predominant component. And it isn't just that we do more learning than most animals; we even do it in more different ways!

All learning ultimately boils down to association and differentiation. These are the two basic mechanisms of learning (and memory) that have been proposed over the centuries. Association is learning that two somethings go together. For example, we learn that spoons go with knives, cups go with saucers, thunder follows lightning, pain follows injury, and so on.

Differentiation is learning to distinguish one something from another. We learn that green, not red, means go, that cats, not dogs, have sharp claws, that soft speech, not yelling, is approved of by one’s elders, that birds have feathers but reptiles don’t. It is clear that association and differentiation are two sides of the same coin, but sometimes one is more obvious, and sometimes the it’s the other.

There are several things that help us to retain associations and differentiations: The first is obvious: Repetition or rehearsal. Practice makes perfect! Then there are things like vividness and intensity: We are more likely to remember someone's name if they are loud and colorful than if they are quiet and ordinary. And finally we have conditioning, that is, associating the whole association or differentiation with something that motivates us, whether it be food, companionship, money, a sense of pride, a fear of pain, or whatever.

The simplest kind of learning, which we share with all animals, we

could

call environmental: On the basis of your present understanding

or

knowledge, you anticipate certain things or act in a certain way - but

the world doesn't meet with your expectations. So, after various other

anticipations and actions, you adapt, develop a new understanding, gain

new knowledge.

Environmental conditioning adds a positive or negative

consequence to the learning that stamps it in: You run, expecting

a 100 yards of open field, when you suddenly smack into a tree you

hadn't noticed. You will be more careful in the future!

For a social animal, much of this learning comes from others - i.e. it is social conditioning, also known as rewards and punishments. So, instead of learning not to run across streets by getting run-over, you learn by getting punished as you begin to run across the street. Or, instead of learning sex roles by accident (!), you are gently shaped by signs of social approval: “My, aren’t you pretty!” or “Here’s my little man!”

Historically, there have been two forms of conditioning that have been the focus of pretty intense study: Classical conditioning and operant conditioning.

Classical conditioning

Classical (or Pavlovian) conditioning builds on reflexes: We begin with an unconditioned stimulus (UCS) and an unconditioned response (UCR) - a reflex! We then associate a neutral stimulus (NS) with the reflex by presenting it with the unconditioned stimulus. Over a number of repetitions, the neutral stimulus by itself will elicit the response! At this point, the neutral stimulus is renamed the conditioned stimulus (CS), and the response is now called the conditioned response (CR).

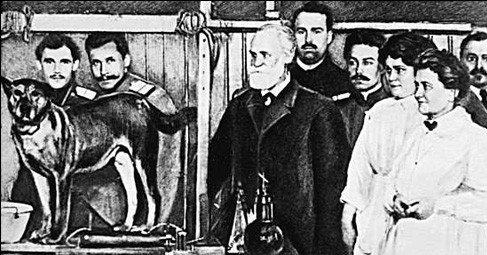

To put it in the form that Pavlov observed

in his dogs: Some

meat

powder on the tongue makes a dog salivate. Ring a bell at the same

time,

and after a few repetitions, the dog will salivate upon hearing the

bell

alone - without being given the meat powder! The dog associates

the ringing of a bell with the presentation of food. The meat

powder

is the unconditioned stimulus and the salivating is, at first, the

unconditioned

response. At first the bell is a neutral stimulus, but after

conditioning,

it becomes the conditioned

stimulus and the salivating becomes the

conditioned

response.

Pavlov (center) with assistants and dog

Classical conditioning can work on any reflex, including the

orienting reflex (which makes you pay attention to new stimuli), the

startle reflex (which makes you jump at disturbing stimuli), emotional

responses (such as fear), and taste aversions (such as a distaste for

sour or bitter).

The first American follower of Pavlov was John Watson. His best

known

experiment was conducted in 1920. “Little” Albert B, an 11 month old

child,

was conditioned to fear a white rat by pairing it with a loud noise

(which leads to the startle reflex, i.e. a good scare). His

fear quickly generalized to white rabbits, fur coats, and even

cotton.

Later, another child, three year old Peter, was gradually

“de-conditioned”

from his fear of white rabbits by pairing white rabbits with milk and

cookies

and other positive things. But we should note that, even if they

didn't "de-condition" him, he would have eventually lost his fear, a

process called extinction.

I

need to add that, as famous as these experiments were, they don't

really qualify as good science, and it appears the results were rather

exaggerated by Watson, who didn't really qualify as a good scientist.

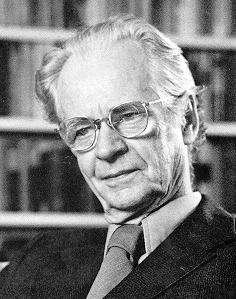

Operant Conditioning

Operant (or Skinnerian) conditioning is based on

consequences:

The organism is in the process of “operating” on the environment, which

in ordinary terms means it is bouncing around its world, doing whatever

it

does.

During this “operating,” the organism encounters a special kind of

stimulus,

called a

reinforcing stimulus, or simply a reinforcer. This

special stimulus has the effect of increasing the likelihood of the

behavior

which occured just before the reinforcer. This is operant conditioning:

Operant (or Skinnerian) conditioning is based on

consequences:

The organism is in the process of “operating” on the environment, which

in ordinary terms means it is bouncing around its world, doing whatever

it

does.

During this “operating,” the organism encounters a special kind of

stimulus,

called a

reinforcing stimulus, or simply a reinforcer. This

special stimulus has the effect of increasing the likelihood of the

behavior

which occured just before the reinforcer. This is operant conditioning:

A behavior followed by a reinforcing stimulus results in an increased probability of that behavior occurring in the future.

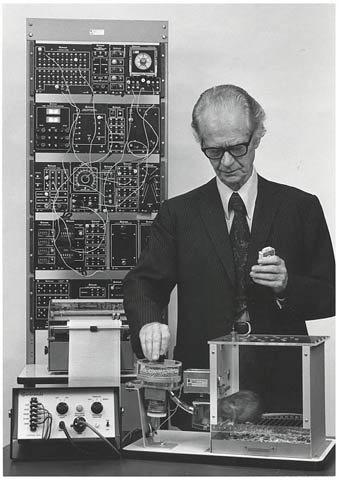

Imagine a rat in a cage. This is a special cage (called, in fact, a

“Skinner box”) that has a bar or pedal on one wall that, when pressed,

causes a little mechanism to release a foot pellet into the cage. The

rat

is bouncing around the cage, doing whatever it is rats do, when he

accidentally

presses the bar and - presto! - a food pellet falls into the

cage!

The operant is the behavior just prior to the reinforcer, which is the

food pellet, of course. In no time at all, the rat is furiously

peddling

away at the bar, hoarding his pile of pellets in the corner of the

cage.

What if you don’t give the rat any more pellets? Apparently, he’s no fool, and after a few futile attempts, he stops his bar-pressing behavior. This is called extinction of the operant behavior.

A behavior no longer followed by the reinforcing stimulus results in a decreased probability of that behavior occurring in the future.

One (of many) interesting discoveries Skinner made has

to do with reinforcement schedules.

If

you want to condition a behavior, the fastest schedule to use is the continuous schedule: Give your dog a

treat every time he does his trick. Of course, this would get

expensive after a while. So give him a treat every fifth time he

does his trick (fixed ratio schedule)

or

if he does his trick at least once within a certain time period (fixed interval schedule).

These work fine, and keeps the behavior from going into extinction.

One (of many) interesting discoveries Skinner made has

to do with reinforcement schedules.

If

you want to condition a behavior, the fastest schedule to use is the continuous schedule: Give your dog a

treat every time he does his trick. Of course, this would get

expensive after a while. So give him a treat every fifth time he

does his trick (fixed ratio schedule)

or

if he does his trick at least once within a certain time period (fixed interval schedule).

These work fine, and keeps the behavior from going into extinction.

Even better, reinforce in some random way. Keep changing the number

of times he has to do his trick to get his treat, or keep changing the

time period on him. These are called variable schedules of reinforcement,

and are very powerful for maintaining something learned by operant

conditioning. This is what keeps gamblers gambling: You

just never know if that next roll of the dice, pull of the arm, or hand

of cards will make you a winner!

Now, if you were to turn the pellet machine back on, so that pressing the bar again provides the rat with pellets, the behavior of bar-pushing will “pop” right back into existence, much more quickly than it took for the rat to learn the behavior the first time. This is because the return of the reinforcer takes place in the context of a reinforcement history that goes all the way back to the very first time the rat was reinforced for pushing on the bar!

A question Skinner had to deal with was how we get to more complex sorts of behaviors. He responded with the idea of shaping, or “the method of successive approximations.” Basically, it involves first reinforcing a behavior only vaguely similar to the one desired. Once that is established, you look out for variations that come a little closer to what you want, reinforce only those, and so on, until you have the animal performing a behavior that would never show up in ordinary life. Skinner and his students have been quite successful in teaching simple animals to do some quite extraordinary things. My favorite is teaching pigeons to bowl!

I used shaping on one of my daughters once. She was about three years old, and was afraid to go down a particular slide. So I picked her up, put her at the end of the slide, asked if she was okay and if she could jump down. She did, of course, and I showered her with praise. I then picked her up and put her a foot or so up the slide, asked her if she was okay, and asked her to slide down and jump off. So far so good. I repeated this again and again, each time moving her a little farther up the slide, and backing off if she got nervous. Eventually, I could put her at the top of the slide and she could slide all the way down and jump off. Unfortunately, she still couldn’t climb up the ladder, so I was a very busy father for a while.

Beyond these fairly simple examples, shaping also accounts for the

most

complex of behaviors. You don’t, for example, become a brain surgeon by

stumbling into an operating theater, cutting open someone's head,

successfully

removing a tumor, and being rewarded with prestige and a hefty

paycheck,

along the lines of the rat in the Skinner box. Instead, you are gently

shaped by your environment to enjoy certain things, do well in school,

take certain bio classes, see an inspiring doctor movie perhaps, have a

good

hospital

visit, enter med school, be encouraged to drift towards brain surgery

as

a speciality, and so on. This could be something your parents were

carefully

doing to you, ala a rat in a cage. But much more likely, this is

something

that was more or less unintentional.

Notice also that sometimes things actually become reinforcers by

association. Money, for example, is highly reinforcing for most

of us. Skinner would explain that by pointing out that,

originally, money was just something that you use to buy things that

are more directly, physically, reinforcing. These learned

reinforcers are called secondary

reinforcers.

And then there is punishment. If you shock a rat for doing x, it’ll do a lot less of x. If you spank Johnny for throwing his toys he will throw his toys less and less (maybe). Punishment usually involves an aversive stimulus, which is the opposite of a reinforcing stimulus, something we might find unpleasant or painful.

A behavior followed by an aversive stimulus results in a decreased probability of the behavior occurring in the future.

On the other hand, if you remove an already active aversive stimulus after a rat or Johnny performs a certain behavior, you are doing negative reinforcement. If you turn off the electricity when the rat stands on his hind legs, he’ll do a lot more standing. If you stop your perpetually nagging when I finally take out the garbage, I’ll be more likely to take out the garbage (perhaps). You could say it “feels so good” when the aversive stimulus stops, that this serves as a reinforcer! This is how a cat or a dog (or you) learns to come in out from the rain.

Behavior followed by the removal of an aversive stimulus results in an increased probability of that behavior occurring in the future.

Notice how difficult it can be to distinguish some forms of negative reinforcement from positive reinforcement: If I starve you, is the food I give you when you do what I want a positive - i.e. a reinforcer? Or is it the removal of a negative - i.e. the aversive stimulus of hunger?

Skinner (contrary to some stereotypes that have arisen about behaviorists) didn’t approve of the use of aversive stimuli - not because of ethics, but because it doesn’t work very well! Notice that I said earlier that Johnny will maybe stop throwing his toys, and that I perhaps will take out the garbage? That’s because whatever was reinforcing the bad behaviors hasn’t been removed, as it would’ve been in the case of extinction. This hidden reinforcer has just been “covered up” with a conflicting aversive stimulus. So, sure, sometimes Johnny will behave - but it still feels good to throw those toys! All Johnny needs to do is wait till you’re out of the room, or find a way to blame it on his brother, or in some way escape the consequences, and he’s back to his old ways.

Higher forms of learning

Not everyone got caught up in the spirit of behaviorism,

though. The Gestalt psychologists (the same ones who explored

perception) noticed that a lot of the "behavior" didn't have to

actually happen physically: People could cognitively work their

way through a problem. This was labelled insight learning. One of the

original Gestaltists, Wolfgang Köhler, got stuck on one of the

Canary Islands off of Africa during World War I. While there, he

studied the local chimpanzees. He would set up problems for them

to solve, such as hanging bananas out of reach. The Chimps would

quickly learn to use some of the things he provided for them, like

boxes they could stack or poles they could insert into other poles to

make longer ones. One chimp in particular, named Sultan, was

particularly good at solving these problems. He would literally

sit and think about the situation, then suddenly get up and create a

new tool to get the object of his desires - the bananas.

Even some behaviorists were interested in atypical examples of

learning. E. C. Tolman, for example, noted that rats, like

people, can learn about their environment without any obvious

reinforcement. Put a rat in a maze and let him wander.

Later, introduce some kind of reward

at the end, and the rats will get to it in no time at all. They

had,

of course, already learned the maze. He called the learning latent learning, and suggested that

the rats had formed a cognitive map

in their little minds, just like you or I might learn to get around an

unfamiliar city without necessarily being rewarded!

Another ability common to social animals is the ability to learn by observing others. There is, for example, vicarious learning: If you see a fellow creature get hurt or do well, get punished or rewarded, etc., for some action, you can "identify" with that fellow creature and learn from it's experiences.

Even more important is the ability called imitation (sometimes called modeling). We not only learn about the consequences of behaviors by watching others (as in vicarious learning), we learn the behaviors themselves as well! Parents are often uncomfortably surprised by how much their children turn out to be just like them, despite all their efforts to turn them into better people. And children are often surprised at how similar they are to their parents, despite all their efforts to turn out different. I would say that imitation is the single most significant way people learn.

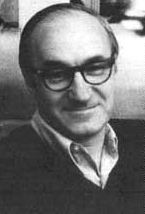

The person most famous for his studies of

imitation is Albert

Bandura.

And, of the hundreds of studies Bandura was responsible for, one group

stands out above the others - the bobo doll studies. He

made a film of one of his students, a young woman, beating up a

bobo doll. In case you don’t know, a bobo doll is a large

inflatable,

egg-shape balloon creature with a weight in the bottom that makes it

bob

back up when you knock him down. Nowadays, it might have Darth

Vader

painted on it, but back then it was “Bobo” the clown.

The person most famous for his studies of

imitation is Albert

Bandura.

And, of the hundreds of studies Bandura was responsible for, one group

stands out above the others - the bobo doll studies. He

made a film of one of his students, a young woman, beating up a

bobo doll. In case you don’t know, a bobo doll is a large

inflatable,

egg-shape balloon creature with a weight in the bottom that makes it

bob

back up when you knock him down. Nowadays, it might have Darth

Vader

painted on it, but back then it was “Bobo” the clown.

The woman punched the clown, shouting “sockeroo!” She kicked

it,

sat on it, hit with a little  hammer, and so on, shouting

various

aggressive

phrases. Bandura showed his film to groups of kindergartners who,

as you might predict, liked it a lot. They then were let out to

play.

In the play room, of course, were several observers with pens and

clipboards

in hand, a brand new bobo doll, and a few little hammers.

hammer, and so on, shouting

various

aggressive

phrases. Bandura showed his film to groups of kindergartners who,

as you might predict, liked it a lot. They then were let out to

play.

In the play room, of course, were several observers with pens and

clipboards

in hand, a brand new bobo doll, and a few little hammers.

And you might predict as well what the observers recorded: A lot of little kids beating the daylights out of the bobo doll. They punched it and shouted “sockeroo,” kicked it, sat on it, hit it with the little hammers, and so on. In other words, they imitated the young lady in the film, and quite precisely at that.

This might seem like a real nothing of an experiment at first, but consider: These children changed their behavior without first being rewarded for approximations to that behavior! And while that may not seem extraordinary to the average parent, teacher, or casual observer of children, it didn’t fit so well with standard behavioristic learning theory, Pavlovian or Skinnerian!

For a social animal capable of language, social learning can be even further removed from immediate environmental feedback. We can, for example, learn by means of warnings, recommendations, threats, and promises. Even creatures without language can communicate these things (through growls and purrs and hisses and the like). But language turns it into a fine art.

And finally, we can learn from descriptions of behaviors, which we can "imitate" as if we had observed them, for example when we read a “how to” book (preferably for “dummies!”). This is usually called symbolic learning. Further, we can learn whole complexes of behaviors, thoughts, and feelings such as beliefs, belief systems, attitudes, and values. It's curious how much we talk about conditioning and modeling in psychology, when we spend so much of our lives in school - that is, involved in symbolic learning!

© Copyright 2002, 2009, C. George Boeree