Phenomenological Existentialism

Dr. C. George Boeree

Phenomenological Existentialism

Dr. C. George Boeree

Phenomenology is a research technique that involves the careful description of aspects of human life as they are lived; Existentialism, deriving its insights from phenomenology, is the philosophical attitude that views human life from the inside rather than pretending to understand it from an outside, "objective" point-of-view. Phenomenological existentialism, as a philosophy or a psychology, is not a tightly defined system by any means. And yet its adherents are relatively easily identified by their emphasis on the importance of individuals and their freedom to participate in their own creation. It is a psychology that emphasizes our creative processes far more than our adherence to laws, be they human, natural, or divine.

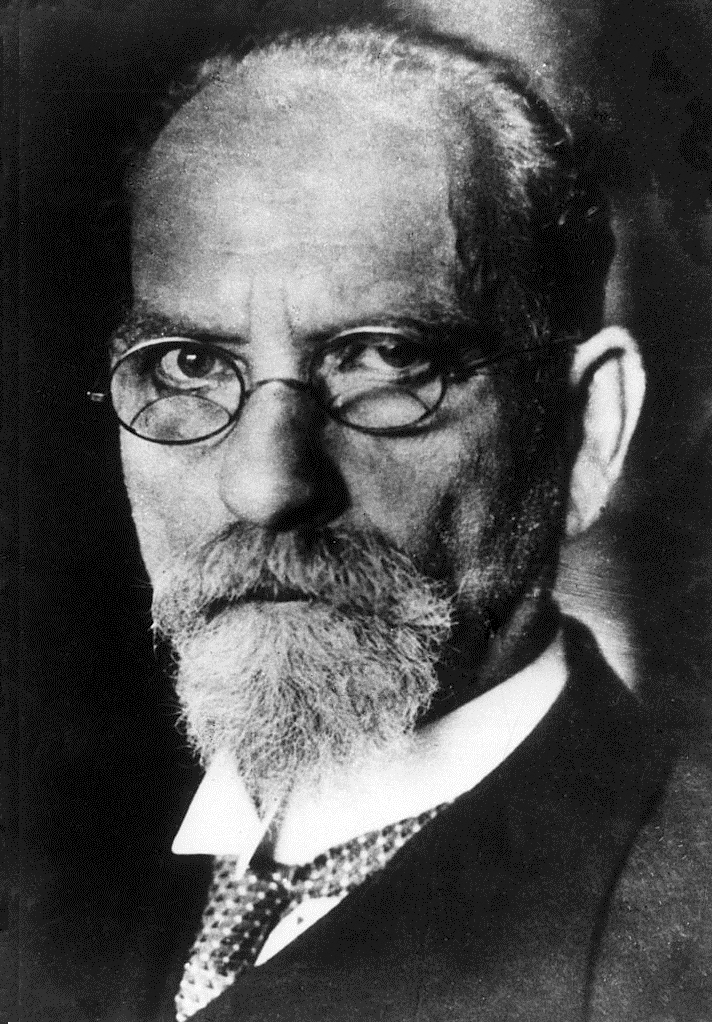

Franz Brentano

Franz Brentano was born January 16, 1838 in

Marienberg, Germany.

He became a priest in 1864 and began teaching two years later at the

University

of Würzburg. Religious doubts led him to leave the priesthood and

resign from his teaching position in 1873.

Franz Brentano was born January 16, 1838 in

Marienberg, Germany.

He became a priest in 1864 and began teaching two years later at the

University

of Würzburg. Religious doubts led him to leave the priesthood and

resign from his teaching position in 1873.

The following year, he wrote Psychology from an Empirical Standpoint. It was in this book that he introduced the concept that is most associated with him: intentionality or immanent objectivity. This is the idea that what makes mind different from things is that mental acts are always directed at something beyond themselves: Seeing implies something seen, willing means something willed, imagining implies something imagined, judging points at something judged. Intentionality links the subject and the object in a very powerful way. He was given a position as professor at the University of Vienna soon after.

In 1880, he tried to marry, but his marriage was forbidden by the Austrian government, who still considered him a priest. He left his professorship and moved to Leipzig to get married. The next year, he was permitted to come back to the University of Vienna, as a lecturer.

He was quite popular with students. Among them were Carl Stumpf and Edmund Husserl, the founders of phenomenology, and Sigmund Freud himself. Brentano retired in 1895, but continued to write until his death on March 17, 1917, in Zurich.

Carl Stumpf

Carl Stumpf was born April 21, 1884 in Wiesentheid in Bavaria. He was strongly influenced by Brentano. As lecturer at the University of Göttingen, he published The Psychological Origins of Space Perception in 1870. In 1873, he became a professor at the University of Wurzburg. His masterwork, Tone Psychology, was completed during a series of professorships at Prague, Halle, and Munich.

He became a professor and the director of the institute of experimental psychology at the Friedrich-Wilhelm University in Berlin in 1894, where he continued his work on the psychology of music, started a journal on the subject, and began an archive of primitive music.

Stumpf retired in 1921, continuing his work until his death on December 15, 1936, in Berlin. With Husserl, he is considered a cofounder of phenomenology and in particular an inspiration to the Gestalt psychologists.

Edmund Husserl

Edmund Husserl was born on April 8, 1859 in Prossnitz, Moravia. He studied philosophy, math, and physics at Leipzig, Berlin, and Vienna and received his doctorate from the University of Vienna in 1882 in mathematics. The next year, he moved to Vienna to study under Franz Brentano.

Husserl, born into a Jewish family, converted to Lutheranism in 1886, and married Malvine Steinschneider in 1887, also a convert. They had three children. In these same years, he went to study with Carl Stumpf at the University of Halle and became a lecturer there. They became good friends and exchanged ideas.

While at Halle, he agonized over the connection between mathematics and the nature of the mind. He recognized that his original ideas, which involved mathematics as coming out of psychology, were misguided. So he began the development of his brand of phenomenology as a way of investigating the nature of experience itself. This led to the publication of Logical Investigations in 1900.

He was invited to a professorship at the University of Göttingen in 1901, where students began to form a circle around him and his work. He also developed a friendship with Wilhelm Dilthey, and was influenced by Dilthey’s ideas concerning the historical context of science.

In 1916, he went to the University of Freiburg. Here he wrote First Philosophy (1923-4), which outlines his belief that phenomenology offered a means towards moral development and a better world. He received many honors and gave guest lectures at the University of London, the University of Amsterdam, and the Sorbonne, making his ideas available to a new, wider audience.

He retired in 1928. Martin Heidegger, with Husserl’s strong approval, was appointed his successor. As Heidegger’s work developed into the basis of existentialism, Husserl distanced himself from the new movement.

When the Nazis took over in 1933, Husserl, born a Jew, was banned from the university. He nevertheless continued providing support to friends in the resistance. He spoke on the European crisis in Vienna in 1935 despite being under a rule of silence. He also spoke at the University of Prague that year, where his unpublished manuscripts were being collected and cataloged.

His last work, The Crisis of European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology (1936), introduced the concept of Lebenswelt. The next year, he became ill and, on April 27, 1938, he died.

Phenomenology

Phenomenology is an effort at improving our understanding of ourselves and our world by means of careful description of experience. On the surface, this seems like little more than naturalistic observation and introspection. Examined a little more closely, you can see that the basic assumptions are quite different from those of the mainstream experimentally-oriented human sciences: In doing phenomenology, we try to describe phenomena without reducing those phenomena to supposedly objective non-phenomena. Instead of appealing to objectivity for validation, we appeal instead to inter-subjective aggreement.

Phenomenology begins with phenomena -- appearances, that which we experience, that which is given -- and stays with them. It doesn't prejudge an experience as to its qualifications to be an experience. Instead, by taking up a phenomenological attitude, we ask the experience to tell us what it is.

The most basic kind of phenomenology is the description of a particular phenomenon such as a momentary happening, a thing, or even a person, i.e. something full of its uniqueness. Herbert Spiegelberg (1965) outlines three "steps:"

1. Intuiting -- Experience or recall the phenomenon. "Hold" it in your awareness, or live in it, be involved in it; dwell in it or on it.

2. Analyzing -- Examine the phenomenon. Look for... the pieces, parts, in the

spatial sense;

the episodes and sequences,

in the temporal sense;

the qualities and dimensions

of the phenomenon.

settings, environments,

surroundings;

the prerequisites and

consequences

in time;

the perspectives or

approaches

one can take.

cores or foci and fringes

or horizons;

the appearing and

disappearing

of the phenomena;

the clarity of the

phenomenon.

And investigate these many aspects both in their outward forms -- objects, actions, others -- and in their inward forms -- thoughts, images, feelings.

3. Describing -- Write down your description. Write it as if the reader had never had the experience. Guide them through your intuiting and analyzing.

What makes these three simple steps so difficult is the attitude you must maintain as you perform them. First, you must have a certain respect for the phenomenon. You must take care that you are intuiting it fully, from all possible "angles," physically and mentally, and leaving nothing out of the analysis that belongs there. Herbert Spiegelberg said "The genuine will to know calls for the spirit of generosity rather than for that of economy...."*

Included in this "generosity" is a respect for both public and private events, the "objective" and the "subjective." A basic point in phenomenology is called intentionality, which refers to the mutuality of the subject and the object in experience: All phenomena involve both an intending act and an intended object. Traditionally, we have emphasized the value of the object-pole and denigrated that of the subject-pole. In fact, we have gone so far as to dismiss even the object-pole if it doesn't correspond to some physical entity! But, to quote Spiegelberg again, "Even merely private phenomena are facts which we have no business to ignore. A science which refuses to take account of them as such is guilty of suppressing evidence and will end with a truncated universe."*

On the other hand, we must also be on guard against including things in our descriptions that don't belong there. This is the function of bracketing: We must put aside all biases we may have about the phenomenon. When you have a prejudice against a person, you will see what you expect, rather than what is there. The same applies to phenomena in general: You must approach them without theories, hypotheses, metaphysical assumptions, religious beliefs, or even common sense conceptions. Ultimately, bracketing means suspending judgement about the "true nature" or "ultimate reality" of the experience -- even whether or not it exists!

Although the description of individual phenomena is interesting in its own right -- and when it involves people or cultures, a massive undertaking as well -- we usually come to a point where we want to say something about the class the phenomenon is a part of. In phenomenology, we talk about seeking the essence or structure of something. So we might investigate the essence of traingularity, or of pizza, or of anger, or of being male or female. We might even, as the phenomenological existentialists have attempted, seek the essence of being human!

Husserl suggested a method called free imaginative variation: When you feel you have a description of the essential characteristics of a category of phenomena, ask yourself, "What can I change or leave out without losing the phenomenon? If I color the triangle blue, or construct it out of Brazilian rosewood, do I still have a triangle? If I leave out an angle, or curve the sides, do I still have a triangle?" This may seem trivial and easy, but now try it regarding "being human:" Is a corpse human? A disembodied spirit? A person in a permanent coma? A porpoise with intelligence and personality? A just-fertilized egg? A six-month old fetus?

With phenomenology, the world regains some of its solidity, the mind is again permitted a reality of its own, and a rather paranoid skepticism is replaced with a more generous, and ultimately more satisfying, curiosity. By returning, as Husserl (1965, 1970) put it, to "the things themselves," or, to use another of his terms, to the lived world (Lebenswelt), we stand a better chance of developing a true understanding of our human existence.

Martin Heidegger

Martin Heidegger was born on September 26,

1889, in Messkirch, Germany.

His father was the sexton of the local church, and Heidegger followed

suit

by joining the Jesuits. He studied the theology and philosophy of

the Middle Ages, as well as the more recent work of Franz Brentano.

Martin Heidegger was born on September 26,

1889, in Messkirch, Germany.

His father was the sexton of the local church, and Heidegger followed

suit

by joining the Jesuits. He studied the theology and philosophy of

the Middle Ages, as well as the more recent work of Franz Brentano.

He studied with Heinrich Rickert, a well known Kantian, and with Husserl. He received his doctorate in 1914, and began teaching at the University of Freiburg the following year. Although he was strongly influenced by Husserl’s phenomenology, his interests lay more in the meaning of existence itself.

In 1923, he became a professor at the University of Marburg, and in 1927, he published his masterwork, Being and Time (Sein und Zeit). Influenced by the ancient Greeks as well as Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, and Dilthey, as well as Husserl, it was an exploration of the verb “to be,” particularly from the standpoint of a human being in time. Densely and obscurely written, it was nevertheless well received all over Europe, though not in the English-speaking world.

In 1928, he returned to Freiburg as Husserl’s successor. In the 1930’s, the Nazi’s began pressuring German universities to fire their Jewish professors. The rector at Freiburg resigned in protest and Heidegger was elected to take his place. Although he strongly encouraged students and professors to be true to their search for truth, he nevertheless also encouraged loyalty to Hitler. He even joined the Nazi party. Many people, otherwise admirers of his thinking, have never forgiven him for that.

To be fair, he did resign from his position as rector in 1934, and after the war talked about Naziism as a symptom of the sickness of modern society. He stopped teaching in 1944, and after the war, the allied forces prevented him from further teaching. But they later restored his right to teach in light of the fact that his support of Hitler was of a passive rather than active nature. He died in Messkirch on May 26, 1976.

Heidegger spent his entire life asking one question: What is it “to be?” Behind all our day-to-day living, for that matter, behind all our philosophical and scientific investigations of that life, how is it that we “are” at all?

Phenomenology reveals the ways in which we are. The first hurdle is our traditional contrast between subject and object, which splits man as knower from his environment as the known. But in the phenomenological attitude, experience doesn’t show this split. Knower and known are both inextricably bound together. Instead, it appears that the subject-object split is something we developed late in history, especially with the advent of modern science.

The problems of the modern world come from the “falling” of western thought: Instead of a concern with the development of ourselves as human beings, we have allowed technology and technique to rule our lives and lead us to a false way of being. This alienation from our true nature is called inauthenticity.

Much of what is difficult about reading Heidegger is that he tries to recover the kind of being that was before the subject-object split by looking at the origins of words, especially Greek words. In as much as the ancient Greeks were less alienated from themselves and their world, their language should offer us a clue to their relation to being.

Heidegger says that we have a special relationship to the world, which he refers to by calling human existence Dasein. Dasein means “being there,” and emphasizes that we are totally immersed in the world, and yet we stand-out (ex-sist) as well. We are a little off-center, you might say, never quite stable, always becoming.

A big part of our peculiar nature is that we have freedom. We create ourselves by choosing. We are our own projects. This freedom, however, is painful, and we experience life as filled with anxiety (Angst, dread). Our potential for freedom calls us to authentic being by means of anxiety.

One of the central sources of anxiety is the recognition that we all have to die. Our limited time here on earth makes our choices far more meaningful, and the need to choose to be authentic urgent. We are, he says, being-towards-death (Sein-zum-Tode).

All too often, we surrender in the face of anxiety and death, a condition Heidegger calls fallenness. We become “das Man” -- “the everybody” -- nobody in particular, the anonymous man, one of the crowd or the mob.

Two characteristics of “das Man” are idle talk and curiosity. Idle talk is small talk, chatter, gossip, shallow interaction, as opposed to true openness to each other. Curiosity refers to our need for distraction, novelty-seeking, busy-body-ness, as opposed to a true capacity for wonder.

We become authentic by thinking about being, by facing anxiety and death head-on. Here, he says, lies joy.

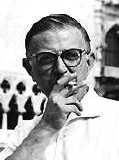

Jean-Paul Sartre

"Man is a useless passion."

Sartre is probably the best known of the

existentialists, and clearly

straddles the line between philosopher and psychologist (and social

activist

as well!). Jean-Paul Sartre was born on June 21, 1905, in Paris,

France, the only child of Jean-Baptiste Sartre and his wife

Anne-Marie.

His father died one year later of colitis, so his mother took him to

live

with her grandfather, Carl Schweitzer, a German professor at the

Sorbonne

and the uncle of the famous missionary-philosopher Albert Schweitzer.

Sartre is probably the best known of the

existentialists, and clearly

straddles the line between philosopher and psychologist (and social

activist

as well!). Jean-Paul Sartre was born on June 21, 1905, in Paris,

France, the only child of Jean-Baptiste Sartre and his wife

Anne-Marie.

His father died one year later of colitis, so his mother took him to

live

with her grandfather, Carl Schweitzer, a German professor at the

Sorbonne

and the uncle of the famous missionary-philosopher Albert Schweitzer.

Rather lost in the disciplined household of her grandfather, Anne-Marie and her small but highly intelligent son grew very close. A childhood illness left Sartre blind in one eye, which drifted outward and up, so he forever seemed to be looking elsewhere. Lonely, he began to write stories and plays as an escape.

Anne-Marie escaped her grandfather's house by getting remarried when Jean-Paul was twelve. Jean-Paul became rebellious and unmanageable, so he was sent to a boarding school. There, he continued his trouble-making ways, and frequently spent time in detention.

After lycée (roughly, high school), Sartre attended the Ecole Normale Superieure at the Sorbonne. Brilliant but disorganized and inattentive, he placed last out of 50 students on his exit exams. The following year, he studied with a young woman named Simone de Beauvoir, and graduated in 1929. He placed first this time, and she second. They would have a strong but open love relationship until their deaths.

After graduation, Sartre taught at a series of lycées for many years. He spent one year in Berlin attending lectures by Edmund Husserl, the founder of phenomenology. This approach would figure prominently in several of his philosophical works, including Imagination (1936), Sketch for a Theory of Emotions (1939), and The Psychology of Imagination (1940)

In 1938, Sartre published his first novel, Nausea. In this novel, he writes about the feelling of nausea that his character feels when he contemplates the "thickness" of the material world, including other people and his own body. The novel is strange, but the descriptions are compelling, and Sartre began to make a name for himself.

In 1939, Sartre was drafted into the army. He was taken prisoner in 1940 and released a year later. His experiences as a participant in the resistance would color many of his later works. In June of 1943, his play The Flies opened in Paris. Even though it was blatantly anti-Nazi, the play was sometimes attended by Nazi officers!

Also in 1943, he published his masterpiece, L'être et le néant (Being and Nothingness). In this large and difficult work, he outlined his theory that human consciousness was a sort of no-thing-ness surrounded by the thickness of being. As a "nothingness," human consciousness is free from determinism, resulting in the difficult situation of our being ultimately responsible for our own lives. "Man is condemned to be free." On the other hand, without an "essence" to provide direction, human consciousness is also ultimately meaningless.

"All existing things are born for no reason, continue through weakness and die by accident.... It is meaningless that we are born; it is meaningless that we die."

Perhaps his best known philosophical point is "existence precedes essence." In the case of non-human entities, an essence is something that is prior to somethings actual existence. A table's essence is the intention that its creator, builder, or user has for it, such as its general shape, components, and function. A woodchuck's essence is in its genetic inheritance, its instincts, and the conditions of its environment -- and its entire life is sort of the playing out of a program. But a human being, according to Sartre, doesn't have a true essence. Oh, sure, we have our general shape, our genetics, our upbringings and the like. But they do not determine our lives, they only set the stage. It is we ourselves who shape our lives. We are the ones who choose what to do with the raw materials nature has provided us. We create ourselves. And our "essence" is only clear when our whole life is done. Another way to put it is that our "essence" is our lack of essence; our "essence" is our freedom.

In 1944, he produced one of his most famous play, Huis Clos or No Exit. This play, and several others, present the problem of living with one's fellow man, and are quite pessimistic. "Hell is other people" is the famous quote from No Exit.

After World War II, Sartre became increasingly concerned with the issue of social responsibility. He postulated that being free meant not only being responsible for your own life, but being responsible for the lives of all human beings. He outlined this idea in Existentialism and Humanism (1946) and a novel called Les Chemins de la Liberté (Paths of Liberty, 1945, never completed).

"But if existence really does precede essence, man is responsible for what he is. Thus, existentialism's first move is to make every man aware of what he is and to make the full responsibility of his existence rest on him. And when we say that a man is responsible for himself, we do not only mean that he is responsible for his own individuality, but that he is responsible for all men."

Sartre also wrote deep psychological examinations of famous French writers: Baudelaire (1947), Jean Genet (1952), and Flaubert (two of three volumes completed in 1971 and 1972). In these, he looks at these writers from existential, psychoanalytic, and Marxist perspectives, in an effort to create the most complete phenomenological portraits possible. The books are, unfortunately, practically unreadable!

Sartre was an admirer of Karl Marx's writings, and of the Soviet Union. His support of Russian communism ended in 1956 when the Russian army marched into Budapest to stop the Hungarian efforts at independence. (My own family emigrated to the US from the Netherlands in that year, fearful of a third world war.) Still hopeful, he wrote a critical analysis of Marxism in 1960 supporting the fundamental ideas of Marx, but criticizing the Russian form Marxism had taken.

In 1963, he published his autobiography, Les Mots (Words). He was awarded the Nobel Prize the following year, but he refused it on political grounds. Here is an example of his evocative style:

"I'm a dog. I yawn, the tears roll down my cheeks, I feel them. I'm a tree, the wind gets caught in my branches and shakes them vaguely. I'm a fly, I climb up a window-pane, I fall, I start climbing again. Now and then, I feel the caress of time as it goes by. At other times - most often - I feel it standing still. Trembling minutes drop down, engulf me, and are a long time dying. Wallowing, but still alive, they're swept away. They are replaced by others which are fresher but equally futile. This disgust is called happiness."

Toward the end of the 1970's, Sartre's health began to degenerate. His bad habits included smoking two packs of unfiltered French cigarettes a day, heavy drinking, and the use of amphetamines to help him stay awake while writing. He died on April 15, 1980, of lung cancer. Simone de Beauvoir tried to stay with his body and had to be taken away by attendants. His funeral procession was attended by over 50,000 mourners.

This philosophy of existentialism, as difficult as it is to express

and

live, had a great impact on any number of thinkers in this

century.

Among them are philosophers such as Simone de Beauvoir, Albert Camus,

Martin

Buber, Ortega y Gassett, Gabriel Marcel, Paul Tillich, Merleau-Ponty,

psychologists

such as Ludwig

Binswanger, Medard

Boss, Erich

Fromm,

Rollo

May, and Viktor

Frankl, and even the post-modernist movement’s Foucault and

Derrida.

Less directly, existentialism has influenced American psychologists

such

as Carl Rogers.

The influence continues to this day.

*Spiegelberg, Herbert (1965). The Phenomenological Movement. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff.

© Copyright 2000 C. George Boeree