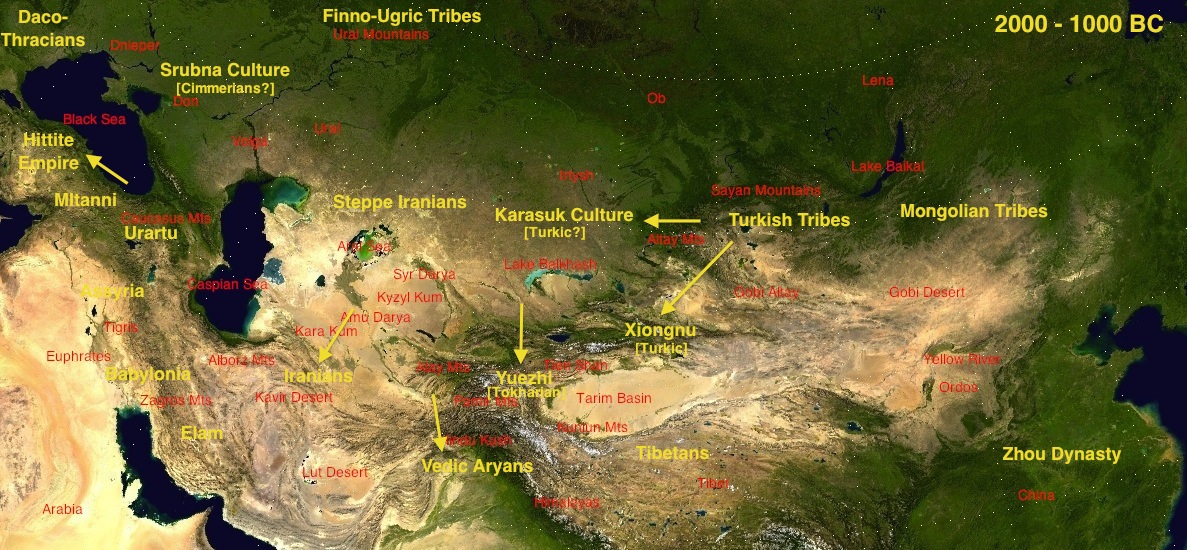

Prehistory of the Steppes

The steppes of Eurasia are essentially open grasslands stretching from the Balkans in southeast Europe to Mongolia. It is not known who the original inhabitants were, but it is likely that they included the ancestors of the Mongols, Turks, Uralic people, and Proto-Indo-Europeans. Originally, after the glaciers of the last ice-age receded, it was sparsely inhabited by hunter-gatherers that followed the herds of large animals and made do with the sparse vegetation of the tundra. As time went by, some people began domesticating both some of the grains and other plants of the steppes and wild animals such as cattle and horses, using techniques learned from more advanced agricultural and pastoral people on the western, eastern, and southern fringes of the grasslands.

The original people of the central steppes north of the Caspian and modern Kazakhstan likely spoke a Proto-Uralic dialect - ancestor to Finnish, Hungarian, Samoyed, etc..

Many inhabited the northern forests as hunter-gatherers, as well as the fishing communities of the Kelteminar culture near the Aral Sea. They were also likely a part of early pastoral societies we often associate with the Proto-Indo-Europeans, such as the Samara and Khvalynsk cultures and those further east. The Proto-Uralics would develop the Pit-Comb culture beginning around

4200 bc, which would extend from both sides of the Ural mountains to Scandinavia.

At around this same time period, Proto-Indo-Europeans (PIE) were developing their own agricultural-pastoral cultures in the Balkans and beyond, and began expanding from the Balkans into what is now the Ukraine. The Dnieper-Donets

culture (~5000 bc, central and western Ukraine) and the Sredny Stog culture (~4000 bc, south-central Ukraine)

represented an ancient eastern PIE dialect, ancestral to the Indo-Iranian, Balto-Slavic, Anatolian, and Tokharian languages.

The eastern PIE people are also favored as the main components of the Samara and Khvalynsk cultures. The open nature of the steppes and the constant movement of mobile tribes lead naturally to considerable intermingling of people with diferent languages, genetics, and cultural traditions.

Further east, the

Botai and Tersek cultures (~3700 bc, north-central Kazakhstan) were perhaps the first to domesticate the horse. It is uncertain what language they spoke. It may have been that of the Uralic people who originally wandered this area, but it might also have been early Tokharian people moving ever farther east, or even a western extension of the Turkic people. A number of words associated with horses and horse culture in IE languages (and Uralic languages as well) seem to have Turkic origins. Prior to the use of horses, the pastoral lifestyle of the steppes primarily involved transhumance, i.e. moving herds of cattle (and horses) from lowlands to highlands and back again with the seasons. With the innovation of horse-riding, the people of the steppes could move herds over much greater distances, and even take their villages with them. As such, culture change and exchange could happen at a much greater pace, and various collections of tribes could become powerful forces.

Note: Most linguists follow Marija Gimbates' Kurgan theory. A smaller group follow Colin Renfrew's Anatolian theory. I am admittedly only an amateur, but I prefer Diakonov's theory, which places the urheimat of the PIE languges in the Balkans.

The Stedny Stog culture would continue

to develop the eastern dialects of PIE. The

proto-Indo-Iranians in particular would move eastward and be primarily responsible for the development of the

extensive Yamna culture (~3600). The Yamna culture would absorb much

of the earlier eastern PIE and proto-Uralic people (and any others that may have lived in the vicinity), as well as drive others even farther east. Although usually associated with PIE, it may have remained linguistically diverse for many centuries. In addition to expanding farther and farther to the east, the Yamna culture also interacted with the Corded Ware cultures of eastern and northern Europe, including later back-migrations.

Of the other eastern PIE people, one group followed the Dniester, Bug, and Dnieper Rivers north to the Vistula and Pripet Rivers, where they would become the Balts and the Slavs. Another group moved along the northern coast of the Black Sea to the Kuban river valley north of

the Caucasus, and developed the Maykop culture (~3700 bc), which thrived

as an intermediary between the Indo-Iranians of the steppes and the more advanced cultures south of the Caucasus. I believe that some portion of the Maykop people would

eventually move into Anatolia to become the Hittites and their

relations. A third group, perhaps beginning in the middle Dnieper valley, would move east along the steppe-forest border until, by 3300 bc,

they would settle as the Afanasevo culture, which many assume to be the proto-Tokharians.

In the following millenium, we see several bronze age Indo-Iranian cultures

develop in the Pontic steppe: the Catacomb culture (~2800 bc) in the Ukraine;

the Poltavka culture (~2700 bc) in the Volga valley; and, north of

the Poltavka culture, the Abashevo culture (~2500 bc), which may

have been Finno-Ugric (i.e. western Uralic - with the related Samoyed people settling east of the Urals).

Deriving from the Poltavka and Abashevo was the Sintashta culture (~2100 bc, at the southern end of the Ural Mountains) and which may have invented the chariot. It would become a part of the broader Andronovo culture (~2000 bc) in what is now Kazakhstan.

Deriving from the Catacomb culture is the Srubna culture (~1800 bc) which ranged from Ukraine to the Ural mountains, west of the still vibrant Andronovo culture. The Srubna culture may have been ancestral to the Cimmerians, who would be pushed back into eastern Europe by the Indo-Iranian Scyths and, eventually, invaded northern Anatolia.

The famous Tarim Basin mummies (in Xinjiang, in western China) - of more European in appearance and

presumed to be Tokharian - are from this time period as well, the

earliest dating to 1800 bc. By the final centuries bc, they became the Yuezhi. They would be displaced by the Turkish Xiongnu, the beginnings of the westward movement of Turkish tribes that would lead them to Anatolia (which would eventually be called Turkey, after the ruling Turks) and domination of central Asia, while the Indo-Europeans of the steppes moved south into the central Asian regions and into southern and south-western Asia.

The Bactrian-Margiana archeological complex, which thrived from 2300 to 1700 aec, was a culture of sedentary farmers living in fortified villages in the area between what is now Kazakhstan and Afghanistan. Their culture was related more to the cultures to the south than to the cultures of the steppes to their north, and they may have been of Dravidian stock. It is possible that the Indo-Iranians raided the farmers of the area over centuries, eventually becoming a dominating group while adopting the farmers' culture (similar to the way that China would, much later, absorb the "barbarian" invaders from the steppes to the west).

From the Bactria-Margiana area, a portion of the Indo-Iranians would eventually (circa 1500 bc) enter the area that is now Syria as the Mittani, a ruling class among the Hurrians. Soon after, other Indo-Iranians would travel from Bactria through the mountain passes into the Swat Valley. There and in neighboring areas, the Aryans, as they called themselves, would prosper and become a commercial and military force to be reckoned with. Aided by the Vedic religious tradition they had developed previously, they would become the ruling class of most of northern India.

The Iranians of the steppes would, in the final millennium bc, expand in many directions: They would move back into eastern Europe as the Scyths and Sarmatians. They would move east to Xinjiang (western China) as the Sakas. And they would move into the Iranian plateau where they would become the Persians, Parthians, and Medes. By the last centuries bc, the Scyths

and their relations would be driven out of the steppes or absorbed by the Turks,

resulting in a spit between the Asian Indo-Europeans and the

European Indo-Europeans that persists to the present.

© 2013, C. George Boeree