C. George Boeree, PhD

Psychology Department

Shippensburg University

© Copyright C. George Boeree 2009, 2011

Moral development

Morality begins with biology, and specifically with the instincts

we

have evolved over eons to aid in our survival and reproduction.

For

human beings, there are three of these instincts:

One is based on kin selection, and it tells us that we should care

for

our closest relatives, especially our children. After all,

caring

for our relatives increases the likelihood of their survival and

reproduction, which in turn increases the likelihood of our genes

-

including the ones that lead us to care for our relatives - get

passed

on to future generations.

The second is the care we feel for our mates. As an animal

that

produces few offspring, requires a nine month gestation

culminating in

a precarious delivery and resulting in a

very vulnerable infant requiring years of care, we have evolved a

strong tendency to develop attachments to our mates. As

any parent can tell you, it takes at least two people to raise

children.

The third is sympathy. We, like many other animals, are

social

creatures, and, like so many prairie dogs, we are attuned to the

emotions and behaviors of our fellow humans. When one of us

is

frightened, the rest go into high alert; when one of us is angry,

we

can rouse the ire of an entire mob; when one of us is laughing,

others

begin to laugh as well - even when they don't get the joke.

Of these three, sympathy is the weakest. In the animal

world,

there are

always "cheaters," animals of the same species who take advantage

of

others who instinctually aid each other. In the human world,

we

have a great many examples of these cheaters, whom we often label

"sociopaths." Also, the tendency to sympathy depends a great

deal

on social learning. It needs to be nourished by

example. In any family where sympathy is lacking, any

instinctual

tendency a child may have can easily be destroyed by abuse or

neglect,

or just self-centered parenting.

As human beings, we have evolved a rather large brain, and one

that is

capable of learning a great many things, not least of which is

language. The ability to learn allows much quicker

adaptation to

environmental change than evolution, and so tends to "drive out"

much

of the hardwiring that animals come supplied with. Certainly

we

still have instincts, but they can be over-written with social

learning

far most easily than in, say, cats and dogs.

A community that has survived and expanded for many decades or

centuries is one which has provided its members with patterns of

thinking, feeling, and behaving that permit that survival.

We

could call these patterns memes, or stick to older words such as

beliefs and techniques - it doesn't matter. Among the

patterns

that appear to work well for most societies are ones that

encourage

extending the range of the instincts of sympathy and love of

family to

all members of the community, rather than just close

relations.

Traditions of mutual respect, obedience to authority, cooperation,

and

so on, are good examples. These traditions make it less

likely

that community members waste their energies on internal conflicts

and

use it instead on productive activities, community defense, and,

possibly, expansion at the expense of other communities.

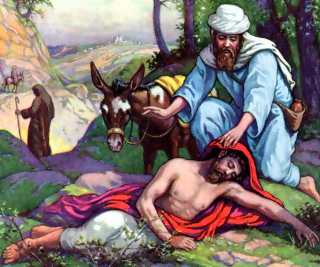

The Hebrews of the Old Testament are a great example of a

community

whose beliefs allowed them to prosper. But when the Bible

says we

should love our neighbor, it clearly meant our neighbor literally,

our

fellow Hebrew, and not, say, Egyptians or Assyrians or Canaanites,

as evidenced by all the rather vicious warfare of the day.

Being

good to one's enemy, someone who is not a member of our "tribe,"

is a

rather novel concept, one, in fact, that makes its appearance only

among

the Jews of Hellenistic times (after Alexander the Great).

After

all, any community that has

the belief that they should be nice even to aggressors, is a

community

that usually doesn't last long and takes that pleasant belief down

with

it.

Although the idea of universal respect had been promoted earlier,

notably by Buddha, Jesus, and Greek philosophers, the movement

that

would be most influential in actualizing the idea would not come

until

the Enlightenment. I believe that this was because it was

only

then that we had essentially filled the planet. Nations and

Empires were

butted up against each other with no room to wiggle. It had

become clear that, if we were to be happy, we could no longer stop

at

making nice with our literal neighbors or our fellow

tribe-mates.

We had to make nice with other nations, other cultures, perhaps

even

everybody! The difficulty here, of course, is that you need

to

convince people to move beyond their instinctive love of family,

beyond

the social indoctrination provided by their tribe, towards

accepting

the fundamental sanity of universal respect.

The great value of this biosocial view of morality is that it

removes

the issue from religious and philosophical debate and places it

squarely in the realm of the pragmatic. Without denying the

inherently subjective nature of our goals as human beings, we may

be

able to agree that one reasonable goal is the maximizing of

happiness. The question is then how do we educate people to

understand that it is in all our best interests to nurture our

innate

tendencies toward compassion.

Traditionally, psychology has avoided studying anything that is loaded with value judgements. There is a degree of difficulty involved in trying to be unbiased about things that involve terms like "good" and "bad!" So, one of the most significant aspects of human life - morality - has had to wait quite a while before anyone in psychology dared to touch it! But Lawrence Kohlberg wanted to study morality, and did so using some of the most interesting (if controversial) techniques. Basically, he would ask children and adults to try to solve moral dilemmas contained in little stories, and to do so outloud so he could follow their reasoning. It wasn't the specific answers to the dilemmas that interested him, but rather how the person got to his or her answer.

One of the most famous of these stories concerned a man named Heinz. His wife was dying of a disease that could be cured if he could get a certain medicine. When he asked the pharmacist, he was told that he could get the medicine, but only at a very high price - one that Heinz could not possibly afford. So the next evening, Heinz broke into the pharmacy and stole the drug to save his wife's life. Was Heinz right or wrong to steal the drug?

There are simple reasons why Heinz should or should not have stolen the drug, and there are very sophisticated reasons, and reasons in between. After looking at hundreds of interviews concerning this and several other stories, Kohlberg outlined three broad levels and six more specific stages of moral development.

Level I: Pre-conventional morality. While infants are essentially amoral, very young children are moral in a rather primitive way described by the two preconventional stages.

Stage 1. We can call this the reward and punishment stage. Good or bad depends on the physical consequences: Does the action lead to punishment or reward? This stage is based simply on one's own pain and pleasure, and doesn't take others into account.Level II: Conventional morality. By the time children enter elementary school, they are usually capable of conventional morality, although they may often slip back into preconventional morality on occasion. But this level is called conventional for a very good reason: It is also the level that most adults find themselves in most of the time!Stage 2. This we can call the exchange stage. In this stage, there is increased recognition that others have their own interests and should be taken into account. Those interests are still understood in a very concrete fashion, and the child deals with others in terms of simple exchange or reciprocity: "I'll scratch your back if you scratch mine." Children in this stage are very concerned with what's fair, but are not concerned with real justice.

Stage 3. This stage is often called the good boy/good girl stage. The child tries to live up to the expectations of others, and to seek their approval. Now the concern includes motives or intentions, and concepts such as loyalty, trust, and gratitude are understood. Children in this stage often adhere to a concrete version of the Golden Rule, although it is limited to the people they actually deal with on a day-to-day basis.Level III: Post-conventional morality. Some adolescents and adults go a step further and rise above moralities based on authority to ones based on reason.Stage 4. This is called the law-and-order stage. Children now take the point of view that includes the social system as a whole. The rules of the society are the bases for right and wrong, and doing one's duty and showing respect for authority are important.

Stage 5. The social contract stage means being aware of the degree to which much of so-called morality is relative to the individual and to the social group they belong to, and that only a very few fundamental values are universal. The person at this level sees morality as a matter of entering into a rational contract with one's fellow human beings to be kind to each other, respect authority, and follow laws to the extent that they respect and promote those universal values. Social contract morality often involves a utilitarian approach, where the relative value of an act is determined by "the greatest good for the greatest number."Stage 6. This stage is referred to as the stage of universal principles. At this point, the person makes a personal commitment to universal principles of equal rights and respect, and social contract takes a clear back-seat: If there is a conflict between a social law or custom and universal principles, the universal principles take precedence.

I can't leave Kohlberg without mentioning his younger colleague

at

Harvard, Carol

Gilligan.

Kohlberg's early research was done at a

boy's school. Later, when girls became part of the research

population, the girls were regularly rated as lower in the stages

than

boys of the same age. Upon investigating further, Gilligan

found

that it was the way in which the girl's expressed themselves that

led

the raters to place them in earlier stages, and that, under

review,

their answers were often at the same or even higher levels than

the

boys. It seems that girls (and women) tend to view moral

situations in terms of relationships and commitment, rather than

in

terms of rules and regulations. That made them appear to be

functioning at level 2 or 3, when in fact they were expressing

something closer to level 5.

Gilligan went a bit further with this than I am comfortable with,

by

suggesting that the differences in moral thinking between males

and

females is tied to genetics, and that female forms of morality are

essentially superior to male forms.

Another psychologist unafraid to tackle morality was Urie Bronfenbrenner. He is famous for his studies of children and schools in different cultures. He outlines five moral orientations:

1. Self-oriented morality. This is analogous to Kohlberg's pre-conventional morality. Basically, the child is only interested in self-gratification and only considers others to the extent that they can help him get what he wants, or hinder him.The next three orientations are all forms of what Kohlberg called conventional morality:

2. Authority-oriented morality. Here, the child, or adult, basically accepts the decrees of authority figures, from parents up to heads of state and religion, as defining of good and bad.The last orientation is analogous to Kohlberg's post-conventional level:3. Peer-oriented morality. This is basically a morality of conformity, where right and wrong is determined not by authority but by one's peers. In western society, this kind of morality is frequently found among adolescents, as well as many adults.

4. Collective-oriented morality. In this orientation, the standing goals of the group to which the child or adult belongs over-ride individual interests. Duty to one's group or society is paramount.

5. Objectively oriented morality. By objectively, Bronfenbrenner means universal principles that are objective in the sense that they do not depend on the whims of individuals or social groups, but have a reality all their own.Bronfenbrenner noted that while 1 is found among children (and some adults) in all cultures, 6 is found in relatively few people in any culture. The differences between 2, 3, and 4 are more a matter of culture than of development. Many cultures promote strict obedience to authority figures. One can see this in some middle eastern cultures, where the word of the religious authorities is law. In many western cultures, conformity to one's peers is a powerful force. And in others still, such as some Asian cultures, the welfare of the group is considered far more important than that of the individual.

Bronfenbrenner also talks about how we get movement from one orientation to another. The movement from 1 to 2, 3, or 4 involves participation in the family and other social structures, where concern for others begins to take precedent over concern for oneself.

Movement from 2, 3, or 4 to 5 occurs when a person is exposed to a number of different moral systems which at least partially conflict with each other, a situation he calls moral pluralism. This forces the person to begin to think about what might lie beneath all the variation, and lead him or her to consider ultimate moral principles.

On the other hand, sometimes people slide back down to the lowest orientation when they suffer from the disintegration of social structures, as in war and other social disasters. This can force a person's attentions back onto their own needs, and cause them to begin ignoring the welfare of larger social groupings.

The first perspective I call the egocentric perspective. I used to call it the autistic perspective, but since I originally wrote about it, the word "autistic" has come to be associated strongly with the disorders of the autistic spectrum. Nevertheless, the egocentric perspective on morality is the perspective held by infants, very young children, perhaps autistic children, and perhaps some psychotic adults. The person taking this perspective sees the world from one point-of-view and one point-of-view only: their own. It is, in other words, purely self-centered. Egocentric morality probably overlaps with Bronfenbrenner's self-oriented morality and at least with Kohlberg's reward-and-punishment stage.

The authoritarian view is a common one - perhaps the most common one. It is a step above the egocentric in that, although it is a subjective view, it takes into account the views of others. In fact, it may be said to absorb the views of others. Developmentally, the simple fact of living among other human beings leads one out of the egocentric into the authoritarian. The child must inevitably broaden his or her perspective to encompass that of significant others, if only to survive. In most circumstances, this process is enormously simplified by the fact that all of a child's immediate contacts share most of a single social reality.

This is the perspective that most fully accepts social

reality.

This means, however, that an authoritarian person accepts only one

social

reality, and understands it as universal. Someone who does

not

accept

the same social reality is seen as either an infant or

insane.

When

this social reality is threatened, either by another social

reality or

by

more immediate experiences, the tendency is for the person to

engage

their defensive mechanisms.

Most children, as well as the adults of primitive or isolated societies, or of highly structured traditional societies, will take this position. There is a tendency to legalistic thinking and an inordinate respect for tradition, even when that tradition is painful. Further, authoritarians tend to classify events, objects, and even people in pigeon-hole types or categories, with relatively few gradations. And they tend to believe in universal dualities - black vs white, good vs bad, us vs them... - with little room for in between or both.

I would divide the authoritarian perspective into four parts: The first part - call it the familial orientation - would be pretty close to Kohlberg's exchange stage plus good girl/good boy stage. The second part would be Bronfenbrenners three social types (authority-oriented, peer-oriented, and collective-oriented moralities).I am personally more interested in adult

forms of morality,

especially those that rise above the authoritarian perspective. So

instead of a single "post-conventional" or "objectively-oriented"

level, I postulate several:

First, there's the rationalistic

perspective. People with this

perspective value reason, words, logic. They seek an objective

truth

that they view as contained within the mind. When someone

who is

brought

up in one of the authoritarian traditions is exposed to other

social

realities beyond their own, they are most likely to seek

commonalities

among those traditions and develop ideal (and often idealistic)

structures to contain them, such as a moral system that extends

beyond

any one culture or society. Rationalistic morality is similar to

Kohlberg's stage of universal principles.

The cybernetic

perspective

is a synthesis of the

rationalistic

and the mechanistic. Instead, it accepts both reason and

empiricism as valid approaches to knowledge, and sees mind and

matter

as

two sides of the same coin. Instead of vast, ethereal

rationalistic theories, or cold, mathematical mechanistic

descriptions,

this perspective tends to try to model

reality - in words, or images,

or computer simulations.

The cybernetic view of morality is, as you might expect, an

interactive

one.

The impact of the valuer becomes important, and moral judgments

are

viewed

as having contexts. It is this view that I think better

accounts

for the highly moral women that Kohlberg's colleague, Carol

Gilligan,

wrote

about. These women, because they kept moral judgments in the

context

of social expectations, individual pains and pleasures, and so

forth,

were

judged by traditional Kohlberg standards as being of rather low

moral

development,

conventional (authoritarian) if not lower. Instead,

she

viewed these women as having a different approach to morality than

the

men, but at the same, or even higher, level. I agree with

Gilligan,

although I don't think this perspective is restricted to women.

Due to my life-long interest in phenomenology, existentialism,

and

Buddhist philosophy, I have come to the conclusion that there are

still

higher perspectives. They may be rare, but every once in a while,

one

comes across a person that seems special - a saint, we might say,

or a

bodhisattva. I have met a few, and read about a few more, as I

suspect

the

reader has as well. Here's my attempt at analyzing these people's

perspectives:

The lower version I call the intersubjective

perspective. As the name implies,

people in this perspective understand what I started this section

with:

That there is one reality and we all have different perspectives

on

that reality. And more: No one person can have a complete

understanding

of the one reality. It's just too big. So the best way to go about

understanding the universe - including ourselves - is to take a

good

look at all the various

ways

of looking at it - that is, being very open-minded

and tolerant - while always staying humble.

Of course, it isn't easy to be this way. For one thing, it's rather impractical. People in the lower perspectives make up their minds (or have their minds made up by others) and get down to the business of making the world fit their beliefs. But intersubjective people, after listening to hundreds of different opinions, can always be persuaded to listen to just one more! Plus, because they are so tolerant, they sometimes seem to pay too much attention to what others may think of as strange or even repulsive ideas. Most of us pay no attention to an ass - but the intersubjective person know that the ass is sometimes right!

The intersubjective perspective views moral value as necessarily

involving consciousness, yet having its own

reality. That is to say, good is to be found in the

interaction

of mind

and world, yet is not to be dismissed as therefore somehow unreal

-

especially

when you consider that all reality, to the extent that we have

anything

to do with it, is a matter of such interaction!

While it is true that the great majority of things that

distinguish

one person from another - or one culture from another - are just a

matter of habits or customs, there are, of course, some things

that are

of moral significance. The intersubjective perspective respects

the

variety of individuals and cultures, but does not shy away from

the

idea that some perspectives are, in fact, morally better than

others.

It recognizes that the good is a direction, not a place, and that

it is

real even though it cannot be expressed in the form of absolutes.

There is one more perspective I can see, even though I'd be the

first

to admit that I am not in it: the transcendental

perspective.

It is even more open, impractical, and, yes, flaky than the

intersubjective,

from the perspective of most of modern society, although primitive

and

traditional societies seem more accepting of it. It

involves,

as the name implies, transcending the multiple perspectives of the

intersubjective

and coming into direct contact with uninterpreted, immediate

reality. This is done

by

stripping away constructed reality altogether, through

techniques such as meditation.

This ultimately involves the diminution of desire and self. That means moving closer and closer to an unconscious state while retaining the ability to recall the experience. In a very real sense, it is a matter of dying - or almost dying - and returning to everyday reality with a new perspective on life.

Since eastern traditions have made quite an impact on the west in

the

last century or so, quite a number of words have become current as

labels

for this perspective: Tao, satori, moksha, buddhahood,

enlightenment,

nirvana,

cosmic consciousness, and so on. A good label is

Maslow's

peak experiences, in that

it

distances the phenomenon from particular

religious

practices and philosophical points of view, and especially

recognizes

that

the experience is one that normal people can have in their

everyday

lives,

not one only available to monks seated in the lotus position. It

describes any experience in which one loses one's sense of

individual

separateness

and feels instead a strong sense of union with all living things.

In the transcendental mode of morality, the good is an expression of one's intimacy with the universe, with the needs of all life, the desire of all consciousness. It is compassion.

The transcendental perspective is very suspicious of words. The

very

first

chapter

of the Tao te Ching, for example, warns us that the Tao that can

be

spoken isn't the true Tao. This said, I will take my own

advice

and cease to

discuss

the transcendental perspective. Or anything else, for that matter...

until the next chapter.