Suggestions regarding the migrations

of the Native Americans

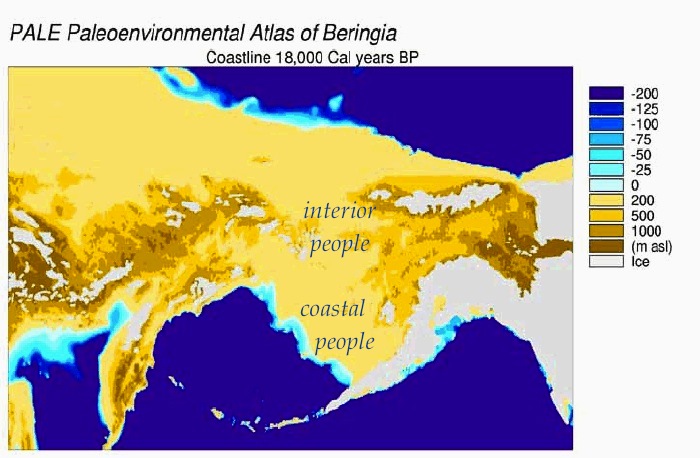

Beringia is the name given to the land that once existed between Siberia and Alaska during the last ice age, when the sea levels were considerably lower than today. It was likely, for the most part, a shrub tundra, with some forest in the south. It was home to a great variety of Arctic mammals, including the megatherians. Sometime between 30,000 bc and 10,000 bc, people moved east and north from Siberia and northern China into Beringia. I suggest that there were two groups:

One stayed closer to the coast and was more dependent on sea and river food sources and had a fairly sophisticated use of boats and had more of the technology common to China, including microblades and fishing paraphenalia.

The other was further north in the interior (the mammoth steppes), and had technologies more similar to that in western Eurasia.They were a much smaller population and would enter North America later.

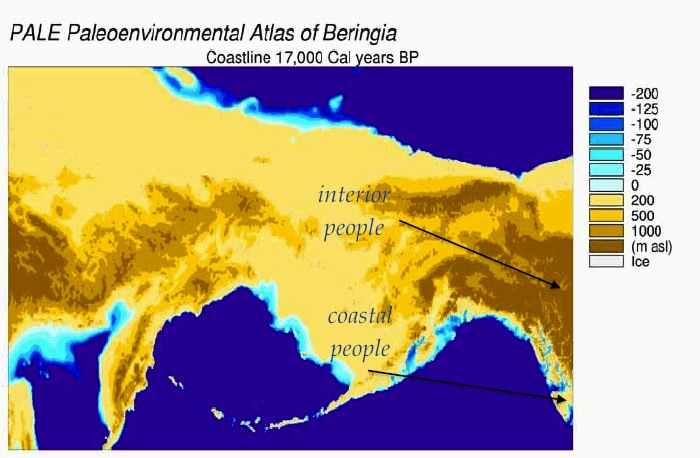

Circa 17,000 bc, as the glacial ice began to retreat, the coastal people began moving south along the Pacific coast, and did so quite rapidly. One branch turned east towards Texas and the Gulf shores of Mexico. The other branch continued down the Pacific coast to South America and all the way to Chile. Later, they would expand east from the coast into the Amazon basin, commonly along river routes. Others would follow the Caribean and Atlantic routes into eastern Brazil.

Most of what Greenberg referred to as the Amerind languages, especially in Mexico, Central America, the Caribbean Islands, and South America, as well as southern and western United States, likely descend from these people.

After 15,000 bc, an ice-free corridor opened east of the Rockies, between the Laurentide and Cordilleran ice sheets. The interior people discovered the corridor and followed the large game animals south and east towards the North American plains. Later, they would enter the eastern woodlands, as well as begin to encounter and mix with the coastal people of the southern plains and Gulf coast.

The Algonquian-speaking people are the most likely descendents of these people. The Siouan and Iroquois people (whom Greenberg included with the Algonquians as the Almosan-Keresiouan language family) might also be descendents.

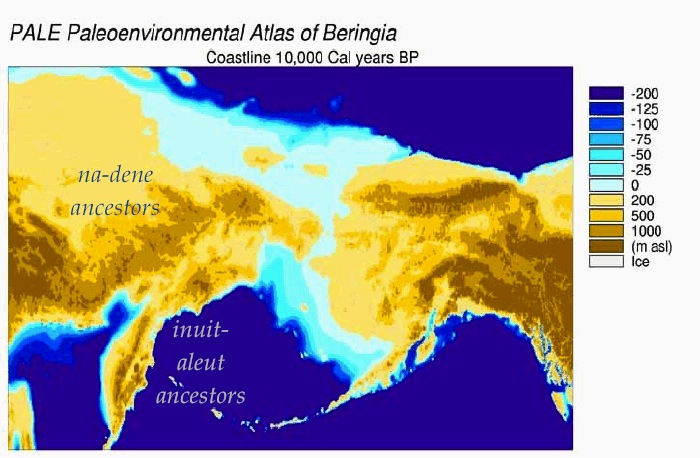

The third group to enter North America were the ancestors of the Na-Dene people. Probably originating in the Yenesei/Baikal area, they crossed the Bering strait and moved into Alaska circa 8,000 bc. Later, they expanded eastward into Alberta and southward along the British Columbia coast. Their languages may be related to the Yeniseian languages of central Siberia, of which only Ket survives.

The fourth group were the ancestors of the Inuits and Aleuts, who probably originated in the Chukotka area, entered Alaska and expanded rapidly across the Arctic coast, eventually ending in Greenland. The first expansion began around 3500 bc (Paleo-Eskimo), and a second one around 1000 ad (the Thule culture), both starting in Alaska. There are still representatives of the Inuit-Aleuts in the Chukchi Peninsula. It has been suggested that their languages are distantly related to the Uralic languages.

The coastal people contributed the most to the genetics of the native American people. Most are in the Q yDNA haplogroup, mostly Q-M3, about 77% in North America and 83% in South America. mtDNA is more varied, but consists primarily of A2, B2, C1, and D1. A is common throughout Asia, with A2 most common in Chukotko-Kamchatka (far-eastern Siberia); B is also common, but the subclade most similar to American B2 is found primarily in South China, Taiwan, and the Philippines; C is found in Siberia, especially among the Yukaghirs and Nganasans; and D is found throughout Asia, especially among the Japanese, Korean, Mongol and Tungus populations. Most Native Americans are blood type O.

Although there is much overlap with the genetics of the coastal people, the descendents of the northeastern interior people have some differences as well. Many of them are in the R1 yDNA haplogroup, with the Ojibwe as high as 79%. Some tribes of Na-Dene people also have as much as 50% R1, as do the Muskogean Seminoles and the Iroquoian Cherokee. The mtDNA includes most of the coastal haplogroups, but among the Algonquian tribes as much as 25% carry the X2a haplotype. Finally, eastern woodland tribes are more likely than others to be blood type A, albeit not as likely as the Na-Dene or Aleut-Inuit.

Because Q yDNA and A, B, C, and D mtDNA are also found in much of eastern and northern Asia (and are by far the most common among native Americans), while R yDNA and X mtDNA are more common in western Eurasia, some have hypothesized that the people of the eastern woodlands descend from Europeans of the Solutrean culture who managed to cross the Atlantic at about the same time as the Beringians entered the Americas. This is supported by the similarity of the Clovis technology to the Solutrean. However, this is not taken seriously by the majority of experts, who believe that the X mtDNA may have more easily derived from central Siberia, and the R yDNA is more likely from European admixture.

Roughly half of the Na-Dene carry the Q yDNA, especially Q-M242 rather than the Q-M3 of other native populations. This suggests that they may be related to the Yenisean people (now represented solely by the Ket). C yDNA is also high - up to 42% - which suggests a relation to the Tungus/Turkic/Mongol people. They have a mix of O and A blood types.

The Aleut-Inuit people tend to be of the Q yDNA group at between 46 and 80%, and have a greater balance of all the blood types. Genetically, they are more similar to the Chukchi and Koryak, as well as some north-eastern Turkic people.

Just as a little thought experiment, I have put together a map of North and South American and some broad classifications of the languages. Please see this map as no more than suggestions and not as factual information!

© 2014, C. George Boeree

Maps from PALE Paleoenvironmental Atlas of Beringia, as presented in Wikipedia; Text added.