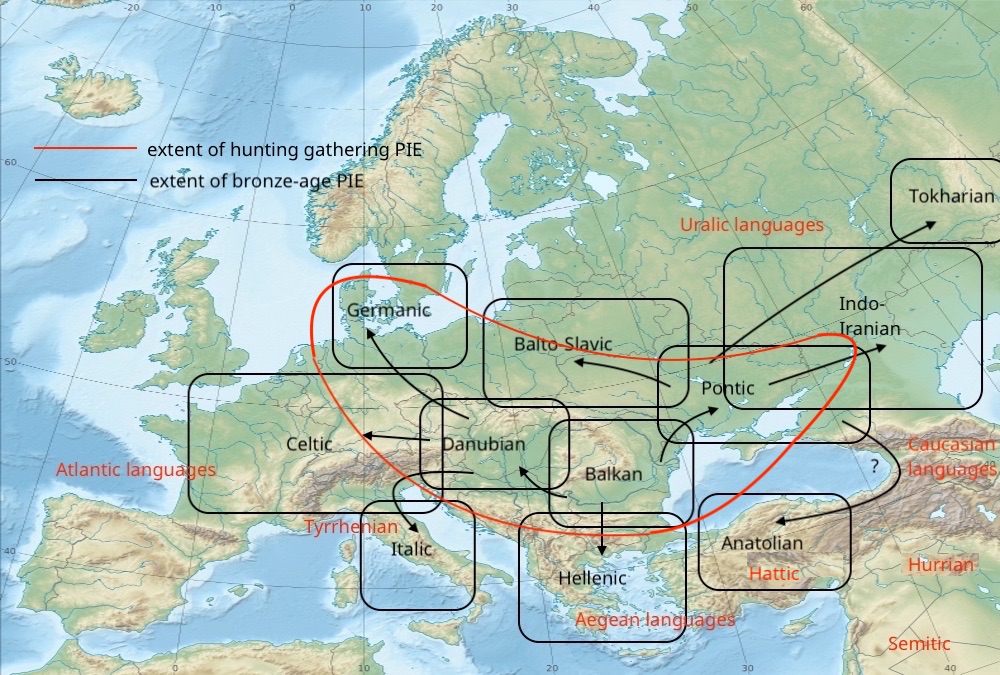

The most likely original home of the PIE-speakers was approximately what we now call Romania, Bulgaria, and Moldova, which served as an ice-age refuge. Other refuges include the Uralic at the southern end of the Ural Mountains, the Vasconic on both sides of the Pyrenees, the Tyrrhenian in Italy, and the Aegean in Greece and the neighboring islands.

As the ice receded, the many people moved towards the north, where game animals - especially large ones - had become plentiful. This included many of the PIE-speakers (or pre-PIE-speakers, if you prefer), who lived the hunting-gathering lifestyle in the areas ranging from the lowlands in the west to the Ukraine steppes to the east.

The PIE people in the Balkans learned agriculture from others to their south. With food reserves and increased populations, they expanded to the areas that were particularly amenable to farming, especially along the Danube towards Hungary and beyond, and along the Black Sea coast to southern Ukraine, more or less dividing this second layer of PIE into a western Danubian dialect, a eastern Pontic dialect, and a central, Balkan, dialect. These dialects were the result, not only of separate development, but of the mingling of the earlier and later dialects, as well as contact with non-PIE people.

The first group to move further east were the ancestors of the Anatolians, who moved along the northern coast of the Black Sea to the Kuban River area, where they would eventually develop the Maykop culture, which prospered as an intermediary between the steppes and the advanced cultures of the Caucasus. Later, a significant portion would invade Anatolia.

At about the same time, the ancestors of the Celts expanded from Hungary into southern Germany via the Danube, and later into France and the Rhine, Meuse, Seine, Loire, and Rhone valleys. Eventually, they would extend across the channel to Britain and over the Pyrenees to Spain and Portugal, absorbing the original inhabitants.

One dialect moved from Hungary into Slovenia and northern Croatia, and eventually into the Po River valley and beyond, to become the Italics.

As the Celts moved west, the ancestors of the Germanics made their way up the Danube and the Elbe, eventually reaching the area we now call Denmark. Later, they would move north into Sweden, and later still, back south into Germany.

Over time, other PIE people entered the Ukraine area. One group moved up the Dniester, the southern Bug, and the Dnieper towards the Vistula, the northern Bug, and the Pripet Marshes. These would become the Balto-Slavic people.

While the Balto-Slavic people moved north, some of the people in the Dnieper valley, perhaps in the neighborhood of modern Kiev, moved east along the forest-steppe border, to become the Tokharians, ultimately reaching the Altai mountains and the Tarim Basin.

Another group also moved into the Ukraine and the steppes and developed a thriving pastoral economy, possibly absorbing other groups along the way. These people, the Indo-Iranians, would come to dominate the steppes for a considerable time, and eventually make their way into Persia and India.

While these groups continued to expand, the Balkan PIE people began to differentiate, with the one group moving south into southern Bulgaria and northern Greece to become the Greeks and related people such as the Macedonians. Another group moved west, via Serbia and Bosnia, towards the Adriatic, to eventually become the Illyrians. And the Thracians spread into the southeast Balkans, leaving the Dacians to dominate what is now Romania.

© 2017 C. George Boeree

As the ice receded, the many people moved towards the north, where game animals - especially large ones - had become plentiful. This included many of the PIE-speakers (or pre-PIE-speakers, if you prefer), who lived the hunting-gathering lifestyle in the areas ranging from the lowlands in the west to the Ukraine steppes to the east.

The PIE people in the Balkans learned agriculture from others to their south. With food reserves and increased populations, they expanded to the areas that were particularly amenable to farming, especially along the Danube towards Hungary and beyond, and along the Black Sea coast to southern Ukraine, more or less dividing this second layer of PIE into a western Danubian dialect, a eastern Pontic dialect, and a central, Balkan, dialect. These dialects were the result, not only of separate development, but of the mingling of the earlier and later dialects, as well as contact with non-PIE people.

The first group to move further east were the ancestors of the Anatolians, who moved along the northern coast of the Black Sea to the Kuban River area, where they would eventually develop the Maykop culture, which prospered as an intermediary between the steppes and the advanced cultures of the Caucasus. Later, a significant portion would invade Anatolia.

At about the same time, the ancestors of the Celts expanded from Hungary into southern Germany via the Danube, and later into France and the Rhine, Meuse, Seine, Loire, and Rhone valleys. Eventually, they would extend across the channel to Britain and over the Pyrenees to Spain and Portugal, absorbing the original inhabitants.

One dialect moved from Hungary into Slovenia and northern Croatia, and eventually into the Po River valley and beyond, to become the Italics.

As the Celts moved west, the ancestors of the Germanics made their way up the Danube and the Elbe, eventually reaching the area we now call Denmark. Later, they would move north into Sweden, and later still, back south into Germany.

Over time, other PIE people entered the Ukraine area. One group moved up the Dniester, the southern Bug, and the Dnieper towards the Vistula, the northern Bug, and the Pripet Marshes. These would become the Balto-Slavic people.

While the Balto-Slavic people moved north, some of the people in the Dnieper valley, perhaps in the neighborhood of modern Kiev, moved east along the forest-steppe border, to become the Tokharians, ultimately reaching the Altai mountains and the Tarim Basin.

Another group also moved into the Ukraine and the steppes and developed a thriving pastoral economy, possibly absorbing other groups along the way. These people, the Indo-Iranians, would come to dominate the steppes for a considerable time, and eventually make their way into Persia and India.

While these groups continued to expand, the Balkan PIE people began to differentiate, with the one group moving south into southern Bulgaria and northern Greece to become the Greeks and related people such as the Macedonians. Another group moved west, via Serbia and Bosnia, towards the Adriatic, to eventually become the Illyrians. And the Thracians spread into the southeast Balkans, leaving the Dacians to dominate what is now Romania.

© 2017 C. George Boeree