C. George Boeree, PhD

Psychology Department

Shippensburg University

© Copyright C. George Boeree 2009

Stages

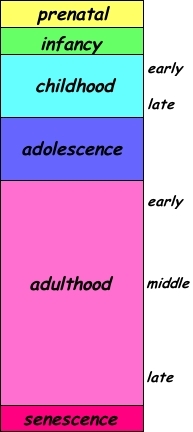

Stages are something most personality theorists shy away from. Sigmund Freud and Erik Erikson are the obvious exceptions, as is the developmentalist Jean Piaget. And yet there is a very biological basis for the idea. We can, on pure biology, separate out at least three stages: the fetus, the child, and the adult. This is parallel to the egg, caterpillar, butterfly example we learned in high school biology.

In addition, we can see three transitional stages: infancy,

adolescence, and senescence.

Senescence is, strictly speaking, the last year or so of a full life, during which time the organs begin to deteriorate and shut down. We don't usually see this as a stage, and in fact most people never reach it, as accidents and diseases usually beat senescence to the punch. But socially speaking, in our culture we certainly prepare ourselves for this inevitability, and that might constitute a social stage, if not a biological one.

As this last point suggests, there are certainly cultural additions we can make. In our culture, there is a sharp transition from preschool child to school child, and another sharp transition from single adult to married adult. For all the power of biology, these social stages can be every bit as powerful.Erikson is most famous for his work in refining and expanding Freud's theory of stages. Development, he says, functions by the epigenetic principle. This principle says that we develop through a predetermined unfolding of our personalities in eight stages. Our progress through each stage is in part determined by our success, or lack of success, in all the previous stages. A little like the unfolding of a rose bud, each petal opens up at a certain time, in a certain order, which nature, through genetics, has determined. If we interfere in the natural order of development by pulling a petal forward prematurely or out of order, we ruin the development of the entire flower.

Each stage involves certain developmental tasks that are psychosocial in nature. Although he follows Freudian tradition by calling them crises, they are more drawn out and less specific than that term implies. The child in grammar school, for example, has to learn to be industrious during that period of his or her life, and that industriousness is learned through the complex social interactions of school and family.

The various tasks are referred to by two terms. The infant's task, for example, is called "trust-mistrust." At first, it might seem obvious that the infant must learn trust and not mistrust. But Erikson made it clear that there it is a balance we must learn: Certainly, we need to learn mostly trust; but we also need to learn a little mistrust, so as not to grow up to become gullible fools!

Each stage has a certain optimal time as well. It is no use trying to rush children into adulthood, as is so common among people who are obsessed with success. Neither is it possible to slow the pace or to try to protect our children from the demands of life. There is a proper time for each task.

If a stage is managed well, we carry away a certain virtue or psychosocial strength which will help us through the rest of the stages of our lives. On the other hand, if we don't do so well, we may develop maladaptations and malignancies, as well as endanger all our future development. A malignancy is the worse of the two, and involves too little of the positive and too much of the negative aspect of the task, such as a person who can't trust others. A maladaptation is not quite as bad and involves too much of the positive and too little of the negative, such as a person who trusts too much.

Jean PiagetAs he continued his investigation of children, he noted that there

were

periods where assimilation dominated, periods where accommodation

dominated,

and periods of relative equilibrium, and that these periods were

similar

among all the children he looked at in their nature and their

timing.

And so he developed the idea of stages of cognitive

development.

These constitute a lasting contribution to psychology.

Freud's biggest contribution to our understanding of personality is

in exploring the effects of parenting on the child's development.

Rather than dwell on Freud's numerous errors in this aspect of his

theorizing, I will provide you with a version which I call "Freud lite."

So, in the oral stage, there comes the task of weaning. At

some point, Mom gets tired of the chore (or gets viciously bitten on

her nipples - ouch!), and the child is encouraged to take solid

foods. Babies are perfectly happy with the original situation,

and resist this change of menu. Some mothers will accept baby's

demands and continue to nurse for months more. Others will demand

right back and force the issue. Freud saw this as a

"crisis." Freud always did have a penchant for drama! But

this step, plus all the other contests of will between parents and

child at this stage, could certainly be considered a task. I

personally doubt that this task will leave any major scars on the

child's psyche, but Freud (and Freudians) do.

Mom and dad, as fully socialized adults, reflect their society, of

course. And society says that one is not permitted to excrete anywhere

at anytime, and must where clothing when in public, and similar

unreasonable demands. So the child needs to be potty

trained. This is not particularly natural (although children will

eventually learn to control these things themselves - just much later

than society prefers), so it can involve some stress on both the

child's and parents' part. Freud focussed on the potty training

issue, but if you generalize a little, you begin to realize that there

are a whole mess of other things as well: washing one's own face,

brushing one's own teeth, getting dressed by oneself, eating neatly on

one's own, picking up one's toys, etc. Call it hygiene

training. The child actually does begin to want to do everything

by themselves, but it often doesn't go as smoothly as desired.

Then there's sex. Of course we aren't talking about adult

ideas of sex (one sincerely hopes). But the distinction between

boys and girls looms large in children's minds around four or five,

most especially in any society where the roles are strongly

marked. Plus,

many children develop that interesting habit of rubbing one's "special

spot," a habit frowned upon by a society like Freud's - or ours.

If you want to know about the Oedipal complex, penis envy, and

castration anxiety, Google them. They are old ideas that are

truly no longer relevant.

Instead, notice that there is a dynamic in the family involving mom,

dad, and child. Once the child learns that girl-boy construct, he or

she will look to mom and dad for the details. Freud's ideas are

rather complicated, but we can simplify easily: boys tend to identify

with dad, and mom serves as a role-reactor, that is, she plays the

"girl" part in the play. Likewise, girls tend to identify with

mom and use dad as a role-reactor. Over time, boys and girls

redirect their affections appropriately. Rather than fear of the

same sex parent (Freud's explanation), we suspect it is simply a matter

of children not being attracted in a physical sense to the people they

are most familiar with. It would be like sleeping with your

brother or sister, and we appear to instinctively find the idea less

than appealing by the time we reach sexual maturity.

Alfred Adler must be credited as the first theorist to include not only a child's mother and father and other adults as early influences on the child, but the child's brothers and sisters as well. His consideration of the effects of siblings and the order in which they were born is probably what Adler is best-known for. I have to warn you, though, that Adler considered birth-order another one of those heuristic ideas-- useful fictions - that contribute to understanding people, but should be not be taken too seriously.

The only child is more likely than others to be pampered, which often leads to being a bit self-centered. After all, the parents of the only child have put all their eggs in one basket, so to speak, and are more likely to take special care - sometimes anxiety-filled care - of their pride and joy. If the parents are abusive, on the other hand, the only child will have to bear that abuse alone.

The first child begins life as an only child, with all the attention to him- or herself. Sadly, just as things are getting comfortable, the second child arrives and "dethrones" the first. At first, the child may battle for his or her lost position. He or she might try acting like the baby - after all, it seems to work for the baby! - only to be rebuffed and told to grow up. Some become disobedient and rebellious, others sullen and withdrawn. Adler believes that first children are more likely than any other to become problem children. More positively, first children are often precocious and more intelligent and tend to be relatively solitary and more conservative than the other children in the family.

The second child is in a very different situation: He or she has the first child as a sort of "pace-setter," and tends to become quite competitive, constantly trying to surpass the older child. They often succeed, but many feel as if the race is never done, and they tend to dream of constant running without getting anywhere. Other "middle" children will tend to be similar to the second child, although each may focus on a different "competitor."

The youngest child is likely to be the most pampered in a family with more than one child. After all, he or she is the only one who is never dethroned! And so youngest children are the second most likely source of problem children, just behind first children. On the other hand, the youngest may also feel incredible inferiority, with everyone older and "therefore" superior. But, with all those "pace-setters" ahead, the youngest can also be driven to exceed all of them.

Who is a first, second, or youngest child isn't as obvious as it

might

seem. If there is a long stretch between children, they may not see

themselves

and each other the same way as if they were closer together. There are

eight years between my first and second daughter and three between the

second and the third: That would make my first daughter an only child,

my second a first child, and my third the second and youngest! And if

some

of the children are boys and some girls, it makes a difference as well.

A second child who is a girl might not take her older brother as

someone

to compete with; A boy in a family of girls may feel more like the only

child; And so on. As with everything in Adler's system, birth order is

to be understood in the context of the individual's own special

circumstances.

Erikson also had some things to say about the interaction of generations, which he called mutuality. Freud had made it abundantly clear that a child's parents influence his or her development dramatically. Erikson pointed out that children influence their parents' development as well. The arrival of children, for example, into a couple's life, changes that life considerably, and moves the new parents along their developmental paths. It is even appropriate to add a third (and in some cases, a fourth) generation to the picture: Many of us have been influenced by our grandparents, and they by us.

A particularly clear example of mutuality can be seen in the problems of the teenage mother. Although the mother and her child may have a fine life together, often the mother is still involved in the tasks of adolescence, that is, in finding out who she is and how she fits into the larger society. The relationship she has or had with the child's father may have been immature on one or both sides, and if they don't marry, she will have to deal with the problems of finding and developing a future relationship as well. The infant, on the other hand, has the simple, straight-forward needs that infants have, and the most important of these is a mother with the mature abilities and social support a mother should have. If the mother's parents step in to help, as one would expect, then they, too, are thrown off of their developmental tracks, back into a life-style they thought they had passed, and which they might find terribly demanding. And so on....

The ways in which our lives intermesh are terribly complex and very frustrating to the theorist. But ignoring them is to ignore something vitally important about our development and our personalities.Family and society

Our families mostly just reflect our society and culture. Erich Fromm emphasizes that we soak up our society with our mother's milk. It is so close to us that we usually forget that our society is just one of an infinite number of ways of dealing with the issues of life. We often think that our way of doing things is the only way, the natural way. We have learned so well that it has all become unconscious - the social unconscious, to be precise. So, many times we believe that we are acting according to our own free will, but we are only following orders we are so used to we no longer notice them. Fromm outlines two kinds of unproductive families.

1. Symbiotic families.

Symbiosis is the relationship two

organisms

have who cannot live without each

other. In a symbiotic family, some

members

of the family are "swallowed up" by other members, so that they do not

fully develop personalities of their own. The more obvious example is

the

case where the parent "swallows" the child, so that the child's

personality

is merely a reflection of the parent's wishes. In many traditional

societies,

this is the case with many children, especially girls.

The other example is the case where the child "swallows" the parent. In this case, the child dominates or manipulates the parent, who exists essentially to serve the child. If this sounds odd, let me assure you it is common, especially in traditional societies, especially in the relationship between a boy and his mother. Within the context of the particular culture, it is even necessary: How else does a boy learn the art of authority he will need to survive as an adult?

In reality, nearly everyone in a traditional society learns both how to dominate and how to be submissive, since nearly everyone has someone above them and below them in the social hierarchy. But note that, for all that it may offend our modern standards of equality, this is the way people lived for thousands of years. It is a very stable social system, it allows for a great deal of love and friendship, and billions of people live in it still.

2. Withdrawing families. In fact, the main alternative is most notable for its cool indifference, if not cold hatefulness. Although withdrawal as a family style has always been around, it has come to dominate some societies only in the last few hundred years, that is, since the bourgeoisie - the merchant class - arrive on the scene in force.

The "cold" version is the older of the two, found in northern and central Europe and parts of Asia, and wherever merchants are a formidable class. Parents are very demanding of their children, who are expected to live up to high, well-defined standards. Punishment is not a matter of a slap upside the head in full anger and in the middle of dinner; it is instead a formal affair, a full-fledged ritual, possibly involving cutting switches and meeting in the woodshed. Punishment is cold-blooded, done "for your own good." Alternatively, a culture may use guilt and withdrawal of affection as punishment. Either way, children in these cultures become rather strongly driven to succeed in whatever their culture defines as success.

All of the preceding families function by what is usually called the

authoritarian parenting style,

which is, in fact,

the

traditional style of parenting we find all over the world and back as

far

as we can see in history. Parents are the bosses in the family,

and

what they say, goes. The consequences can be harsh - physical

punishment,

verbal browbeating, social ostracism - although this does not mean

there

is not also plenty of love as well.

The other style of withdrawing family is called the permissive (or laissez-faire) style. In this case, the child is pretty much allowed to do whatever they like, and the parent interferes only in emergency situations. While we do see this style in some primitive societies with relatively peaceful and safe environments, it is more often seen in modern societies such as our own.

Changes in attitudes about child rearing have led many people to shudder at the use of physical punishment and guilt in raising children. The newer idea is to raise your children as your equals. A father should be a boy's best buddy; a mother should be a daughter's soul mate. But, in the process of controlling their emotions, the parents become coolly indifferent. They are, in fact, no longer really parents, just cohabitants with their children. The children, now without any real adult guidance, turn to their peers and to the media for their values. This is the modern, shallow, television family!

Two new influences are particularly notable in regards to this new

kind of family structure:

First, school (and other educational systems, such as apprenticeship, in other cultures) takes up a considerable part of a child's day. It is, in a very real sense, a child's job. It also seems that this is, in fact, an appropriate time for education, in that children learn easily (relatively speaking).

And second, television - and all the various media we surround ourselves with today - has a powerful influence on children that we are only now starting to understand a little. With children spending hours every day in front of one kind of screen or another, they are absorbing cultural values at a record rate.

Unfortunately, these values may be considerably different from the values parents would like their children to have: Constant exposure to commercials teaches our kids that having things is the way to happiness; The violence they see, even in cartoons, teaches them that you get what you want by taking it, and that the pain of others is unimportant; The emphasis on appearance and sexuality teaches them that looks are everything and anything is all right if it feels good.

Between TV, movies, magazines, music, and now the internet, parents have their job cut out for them. This may be the first generation of parents who have the odd task of teaching their children one thing, while other powerful social forces are teaching them something else! Sadly, many parents have completely abdicated this responsibility, and allow their kids to see and do whatever they want.What makes up a good, healthy, productive family? Fromm suggests it

is a family where parents take the responsibility to teach their

children

reason in an atmosphere of love. Growing up in this sort of family,

children

learn to acknowledge their freedom and to take responsibility for

themselves,

and ultimately for society as a whole.

This last style is called authoritative, which means that, while the child is given considerable freedom and input into family decision-making, the parent is still clearly the parent. Rules are clearly spelled out and never arbitrary, and punishments "fit the crime" but are not physically or psychological abusive. Psychologists believe that this style is most likely to lead to good development, of course.

Of course, parents are not the only influence. In early childhood, and even in infancy, peers - in the form of siblings and play friends - are quite influential. As we get closer to adolescence, though, they begin to dominate. As most parents can see in their own children, much of childhood seems to involve you children paying less and less attention to what you think and more and more attention to what their friends think. This is, of course, a natural thing for the child to do as they move towards independence.Although science generally avoids making value statements, in the

world

of psychology, one value is comfortably accepted by everyone: We

would like to know how best to raise children to become healthy, happy,

and productive people. This is what the field of developmental

psychology is all about.

Infancy is usually considered the first 2 1/2 years of life. The first two months of infancy is called the neonatal period. At this point, life is mostly a matter of satisfying one's basic needs: Enough milk (preferably mom's), staying warm and dry, and, of course, pooping. Lots and lots of pooping. More seriously, the infant needs to be protected from harm and infection, the latter being the greatest threat at this time of life.

In a way, the neonate is a fetus out of his or her

element. A great deal of neurological development especially is

still

going on. Since the neurons are still reproducing and growing

their

axons, the neonate's nervous system retains a considerable amount of

plasticity,

meaning that there is relatively little specialization of

function.

If damage were to occur to a part of the brain, for example, another

part

of the brain could still take over.

Infancts can see at birth, but they are very nearsighted and can't

coordinate their eye movements. Hearing, on the other hand, is

already at work in the womb, by about the 20th week. Smell and

taste are sharp at birth, and babies have a preference for sweets,

which, not coincidentally, includes breast milk.

In the neonate, we can clearly see the presence of some basic reflexes, such as rooting (searching for mom's nipple) and the startle reflex. We can also see certain instinctual patterns: Infants seem to orient towards faces and voices, especially female ones, and seem to recognize their mother's voice and smell.

There have been many interesting experiments in this regard. They use some interesting special techniques: Some videotape the babies face to keep track of where they are looking and how they are responding; others use a special pacifier that keeps track of the rate of sucking, as babies suck more rapidly when they are experiencing something interesting.

One example of an experiment looked at babies responses to various faces, as represented by masks, similar to the ones pictured here:

The surprising finding was that the babies seemed interested in all the faces - even the "scary" one - except the one consisting of one eye. It would seem that the presence of two eyes is a key feature for infants!

The most important psychological task for the infant is called attachment, meaning the establishment of a tight bond with mom, dad, and other significant people. This is our human version of the imprinting process we see in animals, where a baby animal learns to follow its mother. Since our infants can't walk, they make effective use of their parents' instincts to be attracted to babies, by cooing, gurgling, smiling, and generally acting cute.

Physical touch seems to be crucial to attachment. In

orphanages

in troubled countries, where there may be a significant shortage of

caregivers,

the infants are often deprived of much physical contact with the

nurses.

Even when all their other needs are being met, the infants tend to

become

withdrawn and sickly and even die. As the baby book says, babies

need to be held and cuddled and loved.

Attachment is normally established by 8 months or so. Signs of

attachment include separation anxiety,

which is common between 6 and 18 months old, and stranger anxiety,

which is common

between 8 months and 24 months.

Middle infancy (about 2 to 15 months) is a period of rapid growth and weight gain. The nervous system is clearly pulling its act together, and the infant has a strong drive to move and make noise. Among its needs now are not only the presence of a loving adult, but opportunities to experience the environment and to explore it. And the inborn personality differences called temperaments become very clear.

Gordon Allport says that the infant is working on two tasks: developing a sense of body and self-identity. We all have a body, we feel its closeness, its warmth. It has boundaries that pain and injury, touch and movement, make us aware of. Allport had a favorite demonstration of this aspect of self: Imagine spitting saliva into a cup - and then drinking it down! What’s the problem? It’s the same stuff you swallow all day long! But, of course, it has gone out from your bodily self and become, thereby, foreign to you.

Self-identity also develops in infancy. There comes a point were we recognize ourselves as continuing, as having a past, present, and future. We see ourselves as individual entities, separate and different from others. We even have a name! Will you be the same person when you wake up tomorrow? Of course - we take that continuity for granted.Piaget's first stage is the sensorimotor stage. It lasts from birth to about two years old. As the name implies, the infant uses senses and motor abilities to understand the world, beginning with reflexes and ending with complex combinations of sensorimotor skills.

Between one and four months, the child works on primary circular reactions, where an action of his own which serves as a stimulus to which it responds with the more of the same action, and around and around we go. For example, the baby may suck her thumb. That feels good, so she sucks some more... Or she may blow a bubble. That’s interesting so I’ll do it again....

Between four and 12 months, the infant turns to secondary circular reactions, which involve an act that extends out to the environment: She may squeeze a rubber duckie. It goes “quack.” That’s great, so do it again, and again, and again. She is learning what Piaget called “procedures that make interesting things last.”

At this point, other things begin to show up as well. For example, babies become ticklish, although they must be aware that someone else is tickling them or it won’t work. And they begin to develop object permanence. This is the ability to recognize that, just because you can’t see something doesn’t mean it’s gone! Younger infants seem to function by an “out of sight, out of mind” schema. Older infants remember, and may even try to find things they can no longer see.

Between 12 months and 24 months, the child works on tertiary circular reactions. They consist of the same “making interesting things last” cycle, except with constant variation. I hit the drum with the stick -- rat-tat-tat-tat. I hit the block with the stick -- thump-thump. I hit the table with the stick -- clunk-clunk. I hit daddy with the stick -- ouch-ouch. This kind of active experimentation is best seen during feeding time, when discovering new and interesting ways of throwing your spoon, dish, and food.

Around one and a half, the child is clearly developing mental representation, that is, the ability to hold an image in their mind for a period beyond the immediate experience. For example, they can engage in deferred imitation, such as throwing a tantrum after seeing another child throw one an hour ago. They can use mental combinations to solve simple problems, such as putting down a toy in order to open a door. And they get good at pretending. Instead of using a doll as something to sit on, suck on, or throw, now the child will sing to it, tuck it into bed, and so on.Erikson's first stage, infancy or the oral-sensory stage, is also approximately the first year or year and a half of life. The task is to develop trust without completely eliminating the capacity for mistrust.

If mom and dad can give the newborn a degree of familiarity, consistency, and continuity, then the child will develop the feeling that the world - especially the social world - is a safe place to be, that people are reliable and loving. Through the parents' responses, the child also learns to trust his or her own body and the biological urges that go with it.

If the parents are unreliable and inadequate, if they reject the infant or harm it, if other interests cause both parents to turn away from the infants needs to satisfy their own instead, then the infant will develop mistrust. He or she will be apprehensive and suspicious around people.

Please understand that this doesn't mean that the parents have to be perfect. In fact, parents who are overly protective of the child, are there the minute the first cry comes out, will lead that child into the maladaptive tendency Erikson calls sensory maladjustment: Overly trusting, even gullible, this person cannot believe anyone would mean them harm, and will use all the defenses at their command to retain their pollyanna perspective.

Worse, of course, is the child whose balance is tipped way over on the mistrust side: They will develop the malignant tendency of withdrawal, characterized by depression, paranoia, and possibly psychosis.

If the proper balance is achieved, the child will develop the virtue

hope,

the strong belief that, even when things are not going well, they will

work out well in the end. One of the signs that a child is doing well

in

the first stage is when the child isn't overly upset by the need to

wait

a moment for the satisfaction of his or her needs: Mom or dad don't

have

to be perfect; I trust them enough to believe that, if they can't be

here

immediately, they will be here soon; Things may be tough now, but they

will work out. This is the same ability that, in later life, gets us

through

disappointments in love, our careers, and many other domains of life.

Rollo May points out that this is the first point at which we engage

in rebellion (the other

being

adolescence). The child develops his or

her sense of self by means of contrast with adults, from

the “no” of the two year old to the “no way” of the teenager. The

rebellious person wants freedom, but has as yet no full understanding

of

the responsibility that goes with it. The teenager may want to

spend

their allowance in any way they choose - yet may still expect the

parent

to provide the money, and will complain about unfairness if they don't

get it!

Allport suggest that this is the age at which we develop a sense of

self-esteem.

There

also comes a time when we recognize that we have value, to others and

to

ourselves. This is especially tied to a continuing development of

our competencies.

The toddler

Erikson's second stage is the anal-muscular stage of early childhood, from about eighteen months to three or four years old. The task is to achieve a degree of autonomy while minimizing shame and doubt.

If mom and dad (and the other care-takers that often come into the picture at this point) permit the child, now a toddler, to explore and manipulate his or her environment, the child will develop a sense of autonomy or independence. The parents should not discourage the child, but neither should they push. A balance is required. People often advise new parents to be "firm but tolerant" at this stage, and the advice is good. This way, the child will develop both self-control and self-esteem.

On the other hand, it is rather easy for the child to develop instead a sense of shame and doubt. If the parents come down hard on any attempt to explore and be independent, the child will soon give up and assume that they cannot and should not act on their own. We should keep in mind that even something as innocent as laughting at the toddler's efforts can lead the child to feel deeply ashamed, and to doubt his or her abilities.

And there are other ways to lead children to shame and doubt: If you give children unrestricted freedom and no sense of limits, or if you try to help children do what they should learn to do for themselves, you will also give them the impression that they are not good for much. If you aren't patient enough to wait for your child to tie his or her shoe-laces, your child will never learn to tie them, and will assume that this is too difficult to learn!

Nevertheless, a little "shame and doubt" is not only inevitable, but beneficial. Without it, you will develop the maladaptive tendency Erikson calls impulsiveness, a sort of shameless willfulness that leads you, in later childhood and even adulthood, to jump into things without proper consideration of your abilities.

Worse, of course, is too much shame and doubt, which leads to the malignancy Erikson calls compulsiveness. The compulsive person feels as if their entire being rides on everything they do, and so everything must be done perfectly. Following all the rules precisely keeps you from mistakes, and mistakes must be avoided at all costs. Many of you know how it feels to always be ashamed and always doubt yourself. A little more patience and tolerance with your own children may help them avoid your path. And give yourself a little slack, too!

If you get the proper, positive balance of autonomy and shame and doubt, you will develop the virtue of willpower or determination. One of the most admirable - and frustrating - thing about two- and three-year-olds is their determination. "Can do" is their motto. If we can preserve that "can do" attitude (with appropriate modesty to balance it) we are much better off as adults.

The preschoolerStage three is the genital-locomotor stage or play age. From three or four to five or six, the task confronting every child is to learn initiative without too much guilt.

Initiative means a positive response to the world's challenges, taking on responsibilities, learning new skills, feeling purposeful. Parents can encourage initiative by encouraging children to try out their ideas. We should accept and encourage fantasy and curiosity and imagination. This is a time for play, not for formal education. The child is now capable, as never before, of imagining a future situation, one that isn't a reality right now. Initiative is the attempt to make that non-reality a reality.

But if children can imagine the future, if they can plan, then they can be responsible as well, and guilty. If my two-year-old flushes my watch down the toilet, I can safely assume that there were no "evil intentions." It was just a matter of a shiny object going round and round and down. What fun! But if my five year old does the same thing... well, she should know what's going to happen to the watch, what's going to happen to daddy's temper, and what's going to happen to her! She can be guilty of the act, and she can begin to feel guilty as well. The capacity for moral judgement has arrived.

Erikson is, of course, a Freudian, and as such, he includes the Oedipal experience in this stage. From his perspective, the Oedipal crisis involves the reluctance a child feels in relinquishing his or her closeness to the opposite sex parent. A parent has the responsibility, socially, to enourage the child to "grow up - you're not a baby anymore!" But if this process is done too harshly and too abruptly, the child learns to feel guilty about his or her feelings.

Too much initiative and too little guilt means a maladaptive tendency Erikson calls ruthlessness. The ruthless person takes the initiative alright; They have their plans, whether it's a matter of school or romance or politics or career. It's just that they don't care who they step on to achieve their goals. The goals are everything, and guilty feelings are for the weak. The extreme form of ruthlessess is the antisocial personality (better known as the psychopath).

Ruthlessness is bad for others, but is actually relatively easy on the ruthless person. Harder on the person is the malignancy of too much guilt, which Erikson calls inhibition. The inhibited person will not try things because "nothing ventured, nothing lost" and, particularly, nothing to feel guilty about. On the sexual, Oedipal, side, the inhibited person may be impotent or frigid.

A good balance leads to the psychosocial strength of purpose.

A sense of purpose is something many people crave in their lives, yet

many

do not realize that they themselves make their own purposes, through

imagination

and initiative. I think an even better word for this virtue would have

been courage, the capacity for action despite a clear understanding of

your limitations and past failings.

Allport theorizes two aspects of the self that develop during this age: self-extension and self-image. Self-extension develops between four and six. Certain things, people, and events around us also come to be thought of as central and warm, essential to my existence. “My” is very close to “me!” Some people define themselves in terms of their parents, spouse, or children, their clan, gang, community, college, or nation. Some find their identity in activities: I’m a psychologist, a student, a bricklayer. Some find identity in a place: my house, my hometown. When my child does something wrong, why do I feel guilty? If someone scratches my car, why do I feel like they just punched me in the stomach?

Self-image also develops between four and six. This is the “looking-glass self,” the me as others see me. This is the impression I make on others, my “look,” my social esteem or status, including my sexual identity. It is the beginning of what others call conscience, ideal self, or persona.Piaget's preoperational

stage lasts from about two to about seven

years

old, covering both the toddler and preschool stages.

Now that the child has mental representations and is able to pretend, it is a short step to the use of symbols.

A symbol is a thing that represents something else. A drawing, a written word, or a spoken word comes to be understood as representing a real dog. The use of language is, of course, the prime example, but another good example of symbol use is creative play, wherein checkers are cookies, papers are dishes, a box is the table, and so on. By manipulating symbols, we are essentially thinking in a way the infant could not: in the absence of the actual objects involved!

Along with symbolization, there is a clear understanding of past and future. for example, if a child is crying for its mother, and you say “Mommy will be home soon,” it will now tend to stop crying. Or if you ask him, “Remember when you fell down?” he will respond by making a sad face.

On the other hand, the child is quite egocentric during this stage, that is, he sees things pretty much from one point of view: his own! She may hold up a picture so only she can see it and expect you to see it too. Or she may explain that grass grows so she won’t get hurt when she falls.

Piaget did a study to investigate this phenomenon: He would

put children in front of a simple plaster

mountain

range and seat himself to the side, then ask them to pick from four

pictures

the view that he, Piaget, would see. Younger children would pick

the picture of the view they themselves saw; older kids picked

correctly.

Similarly, younger children center on one aspect of any problem or communication at a time. For example, they may not understand you when you tell them “Your father is my husband.” Or they may say things like “I don’t live in the USA; I live in Pennsylvania!” Or, if you show them five black and three white marbles and ask them “Are there more marbles or more black marbles?” they will respond “More black ones!”

Perhaps the most famous example of the preoperational child’s centrism is what Piaget refers to as their inability to conserve liquid volume. If I give a three year old some chocolate milk in a tall skinny glass, and I give myself a whole lot more in a short fat glass, she will tend to focus on only one of the dimensions of the glass. Since the milk in the tall skinny glass goes up much higher, she is likely to assume that there is more milk in that one than in the short fat glass, even though there is far more in the latter. It is the development of the child's ability to decenter that marks him as having moved to the next stageErikson's fourth stage is called the latency stage, and it runs from about six to twelve. The task is to develop a capacity for industry while avoiding an excessive sense of inferiority. Children must "tame the imagination" and dedicate themselves to education and to learning the social skills their society requires of them. Gordon Allport has a very similar idea of this age. He calles it "rational coping," and involves the child developing his or her abilities to deal with life's problems rationally and effectively.

There is a much broader social sphere at work now: The parents and other family members are joined by teachers and peers and other members of he community at large. They all contribute: Parents must encourage, teachers must care, peers must accept. Children must learn that there is pleasure not only in conceiving a plan, but in carrying it out. They must learn the feeling of success, whether it is in school or on the playground, academic or social.

A good way to tell the difference between a child in the third stage and one in the fourth stage is to look at the way they play games. Four-year-olds may love games, but they will have only a vague understanding of the rules, may change them several times during the course of the game, and be very unlikely to actually finish the game, unless it is by throwing the pieces at their opponents. A seven-year-old, on the other hand, is dedicated to the rules, considers them pretty much sacred, and is more likely to get upset if the game is not allowed to come to its required conclusion.

If the child is allowed too little success, because of harsh teachers or rejecting peers, for example, then he or she will develop instead a sense of inferiority or incompetence. An additional source of inferiority Erikson mentions is racism, sexism, and other forms of discrimination: If a child believes that success is related to who you are rather than to how hard you try, then why try?

Too much industry leads to the maladaptive tendency called narrow virtuosity. We see this in children who aren't allowed to "be children," the ones that parents or teachers push into one area of competence, without allowing the development of broader interests. These are the kids without a life: child actors, child athletes, child musicians, child prodigies of all sorts. We all admire their industry, but if we look a little closer, it's all that stands between them and an empty life.

Much more common is the malignancy called inertia. This includes all of us who suffer from the "inferiority complexes" Alfred Adler talked about. If at first you don't succeed, don't ever try again! Many of us didn't do well in mathematics, for example, so we'd rather die than we take another math class. Others were humiliated instead in the gym class, so we never try out for a sport or play a game of raquetball. Others never developed social skills - the most important skills of all - and so we never go out in public. We become inert.

A happier thing is to develop the right balance of industry and

inferiority

-- that is, mostly industry with just a touch of inferiority to keep us

sensibly humble. Then we have the virtue called competency.

The concrete operations stage lasts from about seven to about 11. The word operations refers to logical operations or principles we use when solving problems. In this stage, the child not only uses symbols representationally, but can manipulate those symbols logically. Quite an accomplishment! But, at this point, they must still perform these operations within the context of concrete situations.

The stage begins with progressive decentering. By six or seven, most children develop the ability to conserve number, length, and liquid volume. Conservation refers to the idea that a quantity remains the same despite changes in appearance. If you show a child four marbles in a row, then spread them out, the preoperational child will focus on the spread, and tend to believe that there are now more marbles than before.

Or if you have two five inch sticks laid parallel to each other, then move one of them a little, she may believe that the moved stick is now longer than the other.

The concrete operations child, on the other hand, will know that there are still four marbles, and that the stick doesn’t change length even though it now extends beyond the other. And he will know that you have to look at more than just the height of the milk in the glass: If you pour the milk from the short, fat glass into the tall, skinny glass, he will tell you that there is the same amount of milk as before, despite the dramatic increase in milk-level!

By seven or eight years old, children develop conservation of substance: If I take a ball of clay and roll it into a long thin rod, or even split it into ten little pieces, the child knows that there is still the same amount of clay. And he will know that, if you rolled it all back into a single ball, it would look quite the same as it did - a feature known as reversibility.

By nine or ten, the last of the conservation tests is

mastered:

conservation of area. If you take four one-inch square blocks,

and lay them on a six-by-six cloth together in the center, the

child

who conserves will know that they take up just as much room as the same

squares spread out in the corners, or, for that matter, anywhere at

all. Actually, many adults have trouble with this.

If all this sounds too easy to be such a big deal, test your friends

on conservation of mass: Which is heavier: a million tons

of

lead, or a million tons of feathers? Some of them will "center"

on the words "lead" and "feathers", and not even notice that you

actually said that they each weigh a ton.

In addition, a child learns classification and seriation during this stage. Classification refers back to the question of whether there are more marbles or more black marbles? Now the child begins to get the idea that one set can include another. Seriation is putting things in order. The younger child may start putting things in order by, say size, but will quickly lose track. Now the child has no problem with such a task. Since arithmetic is essentially nothing more than classification and seriation, the child is now ready for some formal education!

AdolescencePuberty is the beginning of adolescence. But when is puberty, exactly? The hormonal changes begin as early as 8 years old. But the physical changes don't usually make themselves known for several years later.

In modern western societies, we usually say that puberty starts between 11 and 12 years old for girls, and between 12 and 13 for boys. 95% of all girls will start somewhere between 8 1/2 and 13, and boys a year or more later, between 9 1/2 and 15.

The first clear sign of puberty for girls is the beginnings of breast development, around the age of 12. There is also an overall growth spurt that begins around 10 1/2, peaks at 12, and begins to slow around 14. But the main mark of puberty is menarche (pronounced MEN-ark-ee), the first period. In modern western societies, it tends to happen between 12 and 13.

Curiously, in 1890, a girl's first period tended to occur at 14 or 15. In 1840, it often began as late as 17! It is thought that this was due to differences in nutrition. Also notice that the average age at which a woman marries today is around 25. In 1890, it was around 22. In the Middle Ages, it could be as young as 12 or 14. (Remember that Romeo and Juliet were only 16!)

The first mark of puberty in boys is the start of testes growth around the age of 13, and penis growth around 14. The growth spurt for boys tends to begin at 12 1/2, peak at 14, and slow by 16 -- hence the common sight of girls towering over their partners at school dances!

The growth spurt we mentioned is about 8 to 10 cm (3 to 4 inches) of height a year for both girls and boys -- similar to the rate of growth back when they were only 2 years old! With this spurt, there is a significant loss of fat in boys, especially in the limbs, which accounts for the common "beanpole" look among adolescents. Girls may also lose fat, but not as dramatically as boys. An unfortunate tendency today, however, is the onset of obesity in adolescence due to the high fat, high sugar diet many teens adopt.

Adolescence is definitely a time of increasing strength: A 14 year old boy has 14 times the number of muscle cells of a 5 year old boy. A 14 year old girl has 10 times the muscle cells of a 5 year old girl.

Psychologically, adolescence is a pretty busy time. Becoming a

sexual adult involves a number of things that may very well have

instinctual

roots: Boys compete with each other for attention with shows of

physical

ability and acts of daring, often bordering on the insane; girls

compete

for the attention of boys, most commonly by attempting to enhance their

appearance. Different cultures have different details, but the

basic

pattern

is pretty universal.

The single most important thing seems to be social acceptance. If you do not have a circle of friends, in the teenage world you are nothing. For many teenagers, whether their isolation is due to a family move or social inhibition, physical abnormalities or not meeting local standards of attractiveness, not being accepted is a cause of depression and sometimes suicide. I believe this response is very likely one we have inherited from our very social pre-human ancestors: If you don't have your group, you might as well be dead.

In later adolescence, two things dominate a teenager's mind:

Finding

a boyfriend or girlfriend and finding a way to make a living. The

way these needs are expressed can range from trying to have sex with

whomever

will have you and making, borrowing, or stealing enough money to make a

good showing, to a serious effort at creating the foundation for a

lifelong

partnership and family based in love and training for a financially and

personally rewarding career.

The end of adolescence is as much a social

thing

as a physiological thing, so it is very hard to say when that is, but

in

western cultures, we usually think of 18 as a convenient mark.

But, with work and family delayed as long as we do, a lot of the

traditional tasks of adolescents continue well into the 20's.

Think about it: Why is it (in the US anyway) you can drive, go to

college, vote for the president, and die in foreign wars when you are

18 - but you can't have a beer till you're 21? You are not

considered mature enough!

Because the adolescent is in the process of breaking away from his or her parents, there is often conflict between them. Ideally, adolescents acknowledge their parents wisdom and politely leave the house, while parent trust their children to make their own decisions and let them go. Unfortunately, it often doesn't work that way. It is almost as if nature is making us so repugnant to each other that we are absolutely eager to go our separate ways.

These conflicts between parents and their adolescent children go back many generations. Socrates and other Greek philosophers complained about this upcoming generation of spoiled slackers, as did writers in the renaissance and all the centuries. Here's a paraphrase of one such complaint:

"Where did you go?"This is a piece of a conversation between a Sumerian youth and his father, recorded in cuneiform some 3 or 4 thousand years ago. (From S. N. Kramer, The Sumerians, University of Chicago Press, 1963.) Funny, I could have sworn I heard this conversation just the other day!

"I did not go anywhere."

"If you did not go anywhere, why do you idle about? Go to school... Do not wander about in the street.... Don't stand about in the public square or wander about the boulevard.... You who wander about in the public square, would you achieve success?... Because my heart had been sated with weariness of you, I kept away from you and heeded not your fears and grumblings.... Because of your clamorings... I was angry with you.... Because you do not look to your humanity, my heart was carried off as if by an evil wind. Your grumblings have put an end to me, you have brought me to the point of death."

According to Erikson, the task during adolescence is to achieve ego identity and avoid role confusion. It was adolescence that interested Erikson first and most, and the patterns he saw here were the bases for his thinking about all the other stages.

Ego identity means knowing who you are and how you fit in to the

rest

of society. It requires that you take all you've learned about life and

yourself and mold it into a unified self-image, one that your community

finds meaningful.

Gordon Allport has a similar view of adolescence: He calls it propriate stiving. This is my self as goals, ideals, plans, vocations, callings, a sense of direction, a sense of purpose. The culmination of propriate striving, according to Allport, is the ability to say that I am the proprietor of my life -- i.e. the owner and operator!

There are a number of things that make things easier: First, we should have a mainstream adult culture that is worthy of the adolescent's respect, one with good adult role models and open lines of communication.

Further, society should provide clear rites of passage, certain accomplishments and rituals that help to distinguish the adult from the child. In primitive and traditional societies, an adolescent boy may be asked to leave the village for a period of time to live on his own, hunt some symbolic animal, or seek an inspirational vision. Boys and girls may be required to go through certain tests of endurance, symbolic ceremonies, or educational events. In one way or another, the distinction between the powerless, but carefree, time of childhood and the powerful and responsible time of adulthood, is made clear.

Without these things, we are likely to see role confusion, meaning an uncertainty about one's place in society and the world. When an adolescent is confronted by role confusion, Erikson says he or she is suffering from an identity crisis. In fact, a common question adolescents in our society ask is a straight-forward question of identity: "Who am I?"

One of Erikson's suggestions for adolescence in our society is the psychosocial moratorium. He suggests you take a little "time out." If you have money, go to Europe. If you don't, bum around the U.S. Quit school and get a job. Quit your job and go to school. Take a break, smell the roses, get to know yourself. We tend to want to get to "success" as fast as possible, and yet few of us have ever taken the time to figure out what success means to us. A little like the young man from an aboriginal tribe, perhaps we need to dream a little.

There is such a thing as too much "ego identity," where a person is so involved in a particular role in a particular society or subculture that there is no room left for tolerance. Erikson calls this maladaptive tendency fanaticism. A fanatic believes that his way is the only way. (Adolescents are, of course, known for their idealism, and for their tendency to see things in black-and-white.) Fanatics will gather others around them and promote their beliefs and life-styles without regard to others' rights to disagree.

The lack of identity is perhaps more difficult still, and Erikson refers to the malignant tendency here as repudiation. They repudiate their membership in the world of adults and, even more, they repudiate their need for an identity. Some adolescents allow themselves to "fuse" with a group, especially the kind of group that is particularly eager to provide the details of your identity: religious cults, militaristic organizations, groups founded on hatred, groups that have divorced themselves from the painful demands of mainstream society. They may become involved in destructive activities, drugs, or alcohol, or you may withdraw into their own psychotic fantasies. After all, being "bad" or being "nobody" is better than not knowing who you are!

If you successfully negotiate this stage, you will have the virtue

Erikson

called fidelity. Fidelity

means loyalty, the ability to live by

societies standards despite their imperfections and incompleteness and

inconsistencies. We are not talking about blind loyalty, and we are not

talking about accepting the imperfections. After all, if you love your

community, you will want to see it become the best it can be. But

fidelity

means that you have found a place in that community, a place that will

allow you to contribute.

The concrete operations child has a hard time applying his new-found logical abilities to non-concrete - i.e. abstract - events. If mom says to junior “You shouldn’t make fun of that boy’s nose. How would you feel if someone did that to you?” he is likely to respond “I don’t have a big nose!” Even this simple lesson may well be too abstract, too hypothetical, for his kind of thinking.

Don’t judge the concrete operations child too harshly, though. Even adults are often taken-aback when we present them with something hypothetical: “If Edith has a lighter complexion than Susan, and Edith is darker than Lily, who is the darkest?” Most people need a moment or two before they can answer.

From around 12 on, we enter the formal operations stage. Here we become increasingly competent at adult-style thinking. This involves using logical operations, and using them in the abstract, rather than the concrete. We often call this hypothetical thinking.

It is the formal operations stage that allows one to investigate a problem in a careful and systematic fashion. Ask a 16 year old to tell you the rules for making pendulums swing quickly or slowly, and he may proceed like this:

A long string with a light weight - let’s see how fast that swings.His experiment - and it is an experiment - would tell him that a short string leads to a fast swing, and a long string to a slow swing, and that the weight of the pendulum means nothing at all!

A long string with a heavy weight - let’s try that.

Now, a short string with a light weight.

And finally, a short string with a heavy weight.

The teenager has learned to group possibilities in four different ways:

By conjunction: “Both A and B make a difference” (e.g. both the string’s length and the pendulum’s weight).On top of that, he can operate on the operations - a higher level of grouping. If you have a proposition, such as “it could be the string or the weight,” you can do four things with it:By disjunction: “It’s either this or that” (e.g. it’s either the length or the weight).

By implication: “If it’s this, then that will happen” (the formation of a hypothesis).

By incompatibility: “When this happens, that doesn’t” (the elimination of a hypothesis).

Identity: Leave it alone. “It could be the string or the weight.”Someone who has developed his or her formal operations will understand that the correlate of a reciprocal is a negation, that a reciprocal of a negation is a correlate, that the negation of a correlate is a reciprocal, and that the negation of a reciprocal of a correlate is an identity (phew!!!).Negation: Negate the components and replace or’s with and’s (and vice versa). “It might not be the string and not the weight, either.”

Reciprocity: Negate the components but keep the and’s and or’s as they are. “Either it is not the weight or it is not the string.”

Correlativity: Keep the components as they are, but replace or’s with and’s, etc. “It’s the weight and the string.”

Maybe it has already occured to you: It doesn’t seem that the

formal operations stage is something everyone actually gets to.

Even

those of us who do don’t operate in it at all times. Even some

cultures,

it seems, don’t develop it or value it like ours does. Abstract

reasoning

is simply not universal.

If you have made it this far, you are in stage six, the stage of young adulthood, which lasts from about 18 to about 30. The ages in the adult stages are much fuzzier than in the childhood stages, and people may differ dramatically. The task of young adulthood is to achieve some degree of intimacy, as opposed to remaining in isolation.

Intimacy is the ability to be close to others, as a lover, a friend, and as a participant in society. Because you have a clear sense of who you are, you no longer need to fear "losing" yourself, as many adolescents do. The "fear of commitment" some people seem to exhibit is an example of immaturity in this stage. This fear isn't always so obvious. Many people today are always putting off the progress of their relationships: I'll get married (or have a family, or get involved in important social issues) as soon as I finish school, as soon as I have a job, as soon as I have a house, as soon as.... If you've been engaged for the last ten years, what's holding you back?

Neither should the young adult need to prove him- or herself

anymore.

A teenage relationship is often a matter of trying to establish

identity

through "couple-hood": Who am I? I'm her boy-friend. The young adult

relationship

should be a matter of two independent egos wanting to create something

larger than themselves.

Our society hasn't done much for young adults, either. The emphasis on careers, the isolation of urban living, the splitting apart of relationships because of our need for mobility, and the general impersonal nature of modern life prevent people from naturally developing their intimate relationships. I am typical of many people in having moved dozens of times in my life. I haven't the faintest idea what has happened to the kids I grew up with, or even my college buddies. My oldest friend lives a thousand miles away. I live where I do out of career necessity and, until recently, have felt no real sense of community.

Before I get too depressing, let me mention that many of you may not have had these experiences. If you grew up and stayed in your community, and especially if your community is a rural one, you are much more likely to have deep, long-lasting friendships, to have married your high school sweetheart, and to feel a great love for your community. But this style of life is quickly becoming an anachronism.

Erikson calls the maladaptive form promiscuity, refering particularly to the tendency to become intimate too freely, too easily, and without any depth to your intimacy. This can be true of your relationships with friends and neighbors and your whole community as well as with lovers.

The malignancy he calls exclusion, which refers to the tendency to isolate oneself from love, friendship, and community, and to develop a certain hatefulness in compensation for one's loneliness.

If you successfully negotiate this stage, you will instead carry

with

you for the rest of your life the virtue or psychosocial strength

Erikson

calls love. Love, in the

context of his theory, means being

able

to put aside differences and antagonisms through "mutuality of

devotion."

It includes not only the love we find in a good marriage, but the love

between friends and the love of one's neighbor, co-worker, and

compatriot

as well.

The seventh stage is that of middle adulthood. It is hard to pin a time to it, but it would include the period during which we are actively involved in raising children. For most people in our society, this would put it somewhere between 30 and 60. The task here is to cultivate the proper balance of generativity and stagnation.

Generativity is an extension of love into the future. It is a concern for the next generation and all future generations. As such, it is considerably less "selfish" than the intimacy of the previous stage: Intimacy, the love between lovers or friends, is a love between equals, and it is necessarily reciprocal. Oh, of course we love each other unselfishly, but the reality is such that, if the love is not returned, we don't consider it a true love. With generativity, that implicit expectation of reciprocity isn't there, at least not as strongly. Few parents expect a "return on their investment" from their children; If they do, we don't think of them as very good parents!

Although the majority of people practice generativity by having and raising children, there are many other ways as well. Erikson considers teaching, writing, invention, the arts and sciences, social activism, and generally contributing to the welfare of future generations to be generativity as well.

Stagnation, on the other hand, is self-absorption, caring for no-one. The stagnant person ceases to be a productive member of society. It is perhaps hard to imagine that we should have any "stagnation" in our lives, but the maladaptive tendency Erikson calls overextension illustrates the problem: Some people try to be so generative that they no longer allow time for themselves, for rest and relaxation. The person who is overextended no longer contributes well. I'm sure we all know someone who belongs to so many clubs, or is devoted to so many causes, or tries to take so many classes or hold so many jobs that they no longer have time for any of them!

More obvious, of course, is the malignant tendency of rejectivity. Too little generativity and too much stagnation and you are no longer participating in or contributing to society. And much of what we call "the meaning of life" is a matter of how we participate and what we contribute.

This is the stage of the "midlife crisis." Sometimes men and women take a look at their lives and ask that big, bad question "what am I doing all this for?" Notice the question carefully: Because their focus is on themselves, they ask what, rather than whom, they are doing it for. In their panic at getting older and not having experienced or accomplished what they imagined they would when they were younger, they try to recapture their youth. Men are often the most flambouyant examples: They leave their long-suffering wives, quit their humdrum jobs, buy some "hip" new clothes, buy a sporty car, and start hanging around singles bars. Of course, they seldom find what they are looking for, because they are looking for the wrong thing!

But if you are successful at this stage, you will have a capacity

for

caring that will serve you

through the rest of your life.

According to the Surgeon General's report (1999), old age should be,

for most of us, a pretty good period in our lives. Our average

life

span is in the 70's, the science of medicine continues to advance, we

are (slowly) becoming more aware of the effects of habits such as

smoking and drinking, the advantages of exercise and a good diet, and

the rewards of continued education and social concern.

Nevertheless,

some 20% of older people have age-related disabilities.

Aging also involves some deterioration of neurological functions. Our reactions are slower, our senses are weaker, our memory isn't what it used to be, and so on. But generally, we should not expect senility as a normal part of aging. Most seniors look forward to retirement as a time when they have more freedom and time to do the things they have postponed in the past. And a person who makes it to 65 can expect another 20 years of life. Given sufficient financial resources and general good health, it can be the "golden years."

This last stage, referred to delicately as late adulthood or maturity, or less delicately as old age, begins sometime around retirement, after the kids have gone, say somewhere around 60. Some older folks will protest and say it only starts when you feel old and so on, but that's an effect of our youth-worshipping culture, which has even old people avoiding any acknowledgement of age. In Erikson's theory, reaching this stage is a good thing, and not reaching it suggests that earlier problems retarded your development!

The task is to develop ego integrity with a minimal amount of despair. This stage, especially from the perspective of youth, seems like the most difficult of all. First comes a detachment from society, from a sense of usefulness, for most people in our culture. Some retire from jobs they've held for years; others find their duties as parents coming to a close; most find that their input is no longer requested or required.

Then there is a sense of biological uselessness, as the body no longer does everything it used to. Women go through a sometimes dramatic menopause; Men often find they can no longer "rise to the occasion." Then there are the illnesses of old age, such as arthritis, diabetes, heart problems, concerns about breast and ovarian and prostrate cancers. There come fears about things that one was never afraid of before - the flu, for example, or just falling down.

Along with the illnesses come concerns of death. Friends die. Relatives die. One's spouse dies. It is, of course, certain that you, too, will have your turn. Faced with all this, it might seem like everyone would feel despair.

In response to this despair, some older people become preoccupied with the past. After all, that's where things were better. Some become preoccupied with their failures, the bad decisions they made, and regret that (unlike some in the previous stage) they really don't have the time or energy to reverse them. We find some older people become depressed, spiteful, paranoid, hypochondriacal, or developing the patterns of senility with or without physical bases.

Ego integrity means coming to terms with your life, and thereby coming to terms with the end of life. If you are able to look back and accept the course of events, the choices made, your life as you lived it, as being necessary, then you needn't fear death. Although most of you are not at this point in life, perhaps you can still sympathize by considering your life up to now. We've all made mistakes, some of them pretty nasty ones; Yet, if you hadn't made these mistakes, you wouldn't be who you are. If you had been very fortunate, or if you had played it safe and made very few mistakes, your life would not have been as rich as is.

The maladaptive tendency in stage eight is called presumption. This is what happens when a person "presumes" ego integrity without actually facing the difficulties of old age. The malignant tendency is called disdain, by which Erikson means a contempt of life, one's own or anyone's.

Someone who approaches death without fear has the strength Erikson calls wisdom. He calls it a gift to children, because "healthy children will not fear life if their elders have integrity enough not to fear death." He suggests that a person must be somewhat gifted to be truly wise, but I would like to suggest that you understand "gifted" in as broad a fashion as possible: I have found that there are people of very modest gifts who have taught me a great deal, not by their wise words, but by their simple and gentle approach to life and death, by their "generosity of spirit."

StrokesWhen many of us notice our slower memories, we think immediately of Alzheimer's. It does, after all, affect somewhere between 8 and 15 percent of people over 65. Memory loss is indeed the most notable feature of Alzheimer's, and can extend to the point of no longer recognizing one's own family. Alzheimer's also includes problems with language, recognizing things, and decision making. Almost inevitably, people become anxious, irritable, and depressed. Who wouldn't. Plus, it is not just hard on the patient. One could argue that it is even harder on the family, especially those charged with daily care.